How one of the best basketball portraits of all time was created.

How one of the best basketball portraits of all time was created.

by Nima Zarrabi

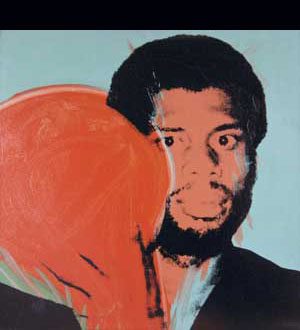

I’m sitting on a plush couch in the living room of the Beverly Hills home of Richard Weisman, staring at the beautiful art on the surrounding walls. My eyes continue to wander over to the next room, as he begins to tell me about The Doc, Julius Erving. I can’t help it. The room once held one of the most important collections of American sports art before disappearing in a theft in early September of last year. In 1977, Weisman had commissioned artist and friend Andy Warhol to produce 10 portraits of stars from the world of sports. In what would be known as The Athletes Series, Warhol photographed the athletes with his Polaroid and then created 40×40 silkscreen portraits as the finished product. “Andy didn’t know the difference between a golf ball and a football,†Weisman says, with a smile. “I had to pick out the athletes.†Each athlete that participated would be given an original as a gift for agreeing to be part of the project.

This is where Dr. J. comes into focus. He was Weisman’s natural choice to represent the game of basketball, but there were issues with the agent for the NBA superstar. “I had it all done with Dr. J, who is a friend of mine,†Weisman tells me. “I would have rather done Kareem, but figured I would do Julius since I knew him. But then his agent comes to me and says, ‘If you want to do Julius Erving’s portrait, you’re going to have to give me one or you’re not going to do it.’ It was unbelievable. Frankly, I was thrilled because I went to Kareem.â€

**

Vincent Fremont worked with Warhol at The Factory for 17 years. He now serves as the exclusive agent for sale of paintings, sculptures and drawings owned by The Andy Warhol Foundation.

In a phone interview from his office in New York, Fremont explained that in the 70s and 80s, it was common for strangers to call Warhol’s studio and set up an appointment for a commissioned work. The money from the commissions helped pay the bills and helped Warhol invest in new technologies such as video equipment. “For the most part, during the 70s and 80s the price was $25,000 for the fist [portrait] and $15,000 for the second,†Fremont says. “Anybody who bought a portrait from Andy, even if it’s an unknown person or an older man, the value has increased no matter what. On behalf of the foundation, I sold portraits of unknown ladies who we couldn’t even find the name for and they sold well.†Although The Athletes Series featured icons from 30 years ago, Fremont believes they still hold immense value. Warhol’s work has always sold well—he is the second most traded artist behind Pablo Picasso. Green Car Crash, a painting by Warhol in 1963 from his Death and Disaster series, sold at a Christie’s New York auction in 2007 for just under $72 million.

**

According to Detective Don Hrycyk of the LAPD art theft detail, Weisman’s home was burglarized sometime between September 2 and 3 of 2009. There was no forced entry and none of the other expensive artwork hanging on adjoining walls was touched, other than the 10 portraits from the series along with a Warhol portrait of Weisman, done in a similar style. “It seems like they were targeted,†Hrycyk says. “There were other Warhols in the home but they were of family members and what not. But for them to take Mr. Weisman’s portrait didn’t really show that they paid a lot of attention to who was depicted. Or they mistook him because it was the same format, the same size, so maybe they assumed they were all athletes.†Weisman was at his residence in Seattle at the time of the theft which was first noticed by a housekeeper.

Prior to the burglary, Weisman owned four sets of The Athlete Series portraits. He had commissioned 8 sets originally for roughly $800,000. Each set is unique with the athletes portrayed in different colors.

Two sets were sold at cost to his father, who donated one set to UCLA and the other to The University of Maryland. One set went to the athletes who participated and another set went to each respective sporting institution, such as the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, MA.

The collection that Weisman kept in his Beverly Hills home was insured for $25 million. Shortly after the theft, a $1million reward was offered for any information leading to the recovery of the artwork. The reward soon dissolved however, after Weisman opted against filing to collect his claim.

**

Warhol was an outsider to the sports world, so securing athletes was not an easy task for Weisman. A few of the athletes had reservations about Warhol, most notably golfer Jack Nicklaus. “He had heard that Andy might be weird,†Weisman recalls. Most of the athletes agreed to the project when they learned that Muhammad Ali was on board. Warhol traveled to Ali’s boxing camp in Deerlake, PA to shoot the Champ, who understood Warhol’s unique place in the pop culture stratosphere and was excited about his selection. “This little negro from Kentucky couldn’t buy a fifteen hundred-dollar motorcycle a few years ago and now they pay twenty-five thousand dollars for my picture!â€

Similar to Ali, Abdul-Jabbar had no reservations about joining the project. “My initial reaction to being chosen to be in Andy Warhol’s athlete series was one of being proud that I was considered to be worthy of that distinction,†Abdul-Jabbar says via email. “I was aware of the fact that Warhol was an artist who had emerged to become one of the trend-setters in modern art.â€

Warhol flew to California to photograph Kareem on November 4, 1977. He was amazed at the center’s sheer size, commenting that he could literally fit between his legs. Abdul-Jabbar remembers Warhol as a relaxed and focused artist, who conducted the session seriously. “When I met with him to pose for the polaroids he used as a study of his subjects, I had an interesting talk with him concerning the impact of his art,†Abdul-Jabbar recalls. “He told me how various images—soup cans, cleaning products—were parodies of the nature of America’s popular culture. It made it possible for me to have an insight as to how Warhol’s images said something about who and what we are as a nation.â€

**

In November of 2007, one of the Ali portraits, considered to be the cornerstone of the collection, came up for auction at Christie’s New York. The artwork was now property from a private Midwest Collection that had purchased the piece from Veronica Ali, who was married to the Champ when the portrait was completed. The pre-auction estimate for the beautiful red and green polymer and silkscreen canvas was $2-3 million. The bidding closed at $9.2 million. The majority of the other works in the series are considered to be worth low to high six figures. Clearly, the optimum value is in the entire set. “What makes them valuable as a set is the fact that if you were trying to put a set together, it wouldn’t be easy to find them at auction,†Fremont explains. “So it’s looked at as a premium.â€

**

Weisman surprised the art world when he decided to forgo the multimillion-dollar insurance policy he had in place for the stolen works. The subsequent investigation by his insurance company, Chartis, would have commenced a thorough investigation into Weisman and his family’s personal records and information. The thought of such an inquiry was considered incredibly intrusive to Weisman, who still maintained ownership of three sets of the series and is in no dire need for money. The LAPD found Weisman’s decision curious, which seemed to anger the prominent art collector who felt the remark may have implied that he had a hand in the theft. He was critical of the department’s art theft detail in an interview with The Seattle Times. Weisman comes from a remarkable family of art collectors. His father Frederick Weisman built a celebrated collection of works that included Warhol, Cezanne and Pollock. His mother Marcia Weisman was a driving force behind the creation of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary art (LACMA).

Detective Hrycyk, a veteran art sleuth who has investigated over 600 cases during the past 15 years, says the investigation remains active and the LAPD is still trying to find out what happened.

“We got along fine,†Hrycyk says of his relationship with Weisman. “I don’t think there was anything that was very intrusive. Of course, when you have an insurance company that’s going to have to pay out $25 million and there’s no sign of forced entry and nothing else taken except these artworks—of course they’re going to start hiring private investigators to try to figure out if there was something funny about the whole thing. Apparently, he didn’t like that process with the insurance company.â€

**

The Athlete Series was intended to merge two of the nation’s most popular leisure activities: sports and art. The paintings have been exhibited in numerous museums throughout the world and consistently draw huge crowds. Weisman’s goal was to expand the horizons of the art world, believing that fans of sport could potentially enter a museum for the first time to see Warhol’s depiction of Ali or Kareem and be moved by the other art held in the museum—a notion that they may have never considered before. “Almost like, art isn’t so bad,†Weisman says. “It’s actually kind of cool.â€

For Warhol, The Athlete Series was an introduction to the sporting landscape, a world he was very unfamiliar with. Following the success of his athlete portraits, Warhol became a fan of hockey and went on to photograph other athletes such as Wayne Gretzky. Warhol had sensed the incredible platform athletes would have in the age of televised sports coverage. “I said that athletes were better than movie stars and I don’t know what I’m talking about because athletes are the new movie stars,†Warhol explained.

The experience was also positive for Kareem. After his Bel Air mansion was destroyed in an electrical fire in 1983, rumors surfaced that Warhol’s painting of the Lakers captain had been lost in the flames. Upon hearing the news, actor Jack Nicholson contacted Weisman to see if he could have Warhol produce another painting for his favorite center. Weisman obliged and Warhol created another Kareem portrait only to find that the original one given to Abdul-Jabbar made it out of the fire safely. “So Jack ended up buying it for himself,†Weisman says. “So Jack’s got one too.â€

And while the Ali painting remains the most valuable of the collection, the image of Kareem may be the most beautiful. “I like Kareem’s portrait a lot,†Fremont says. “I think it’s a really good painting. Andy wouldn’t have done the project if he didn’t like the idea. Andy always had to like what he was doing. If it wasn’t fun then it wasn’t worth doing.â€

Warhol’s experience with Kareem marked the only time in his life that he painted a basketball player, according to Matt Wrbican, archivist of the Andy Warhol Musuem. Abdul-Jabbar noted the impactful history behind the project as a whole. “I think Warhol’s paintings are a milestone in American art and they illuminate the time frame of the 70s,†he says. “I thought my paintings were interesting and faithful to Mr. Warhol’s vision and I was happy with the result.â€

As for the missing set of Warhols, Detective Hyryck remains optimistic that the works will someday be recovered. “Typically we make recoveries when it has gone through several different hands and it’s now in the hands of somebody that doesn’t know its history—doesn’t know it’s stolen,†he says. “And they’ll take it down to the auction house to get the best price possible—they’ll want to be on the front cover of the catalog just for exposure. Then they’re really surprised when they find out it was stolen maybe a decade earlier. We’ve had work show up 50 years after the original theft. It shows that art is one of the best types of property to ultimately recover because the pieces are unique and the suspect usually isn’t going to try and alter the artwork because that would change the value.â€

If you have any information regarding the stolen Warhol artworks, please contact the LAPD art theft detail at (213) 486-6940. For more information about Richard Weisman and his book, Picasso to Pop: The Richard Weisman Collection, visit picassotopop.com