Like most kids in America, I was taught that sports is more than just physical exercise, it’s also where we learn about fair play, self-discipline, how to be a good winner as well as a good loser, and how to bounce back from defeat and disappointment.

Although religion, movies, TV, and novels passively teach us about moral behavior, sports is a visceral hands-on experience filled with emotional drama mixed with blood, sweat, and tears. It challenges us in a high-pressure moment to be our best selves and to do the right thing. Even though we can’t play or watch sports right now, sports has a lot to teach us about how to deal with the coronavirus, from the government’s handling of the crisis to the workers still out there keeping the country running to the people sequestered at home.

With 95 percent of Americans under stay-at-home restrictions, many have undoubtedly felt the strain of living like they’re under house arrest. Most athletes have experience in being injured, sometimes removing them from their sport and livelihood for weeks, months, even years. When I got my eye poked while playing with the Bucks, I ended up missing 16 games (and came back wearing goggles). Peyton Manning had to sit out an entire year after neck injuries and a spinal fusion. Both of us returned to play better than ever. But the depression, the feeling of uselessness, the fear that this is the end of our hopes—no matter how irrational—was real. The way athletes are able to endure the isolation and feelings of helplessness and worthlessness is to fall back on the traits that made them excel in the first place: discipline through visualization.

Feeling isolated because you’re cut off from your friends, family, and co-workers can’t be erased, but it can usually be mitigated by Zooming, phoning, and texting. But feeling helpless in having any control over your life can’t be mitigated as easily. Most of us live our lives according to strict schedules of work, play, and family. When that schedule is thrown off balance, we tend to let everything slip. When we can’t see a clear end, we are more likely to start reaching for the Twinkies rolled in potato chips and deep fried in bacon grease. And promises of finally getting in shape become, “I’ll start tomorrow,†played on an endless loop. Projects you were giddy about at long last completing are back on the “as soon as I finish binging Tiger King/Bosch/Picard†list.

Athletes grow up by visualizing in the short term and the long term. The short term is visualizing winning the next game. Walking onto the court or field and picturing yourself scoring, defending, stealing the ball. The long term is visualizing your college career and even your pro career. You fix it in your mind and do one more set with the weights, ten more wind sprints, twenty more free throws. Now sitting in your living room, picture the stay-at-home over. What would you like to have accomplished? Imagine coming out the other end and sharing how you wrote, painted, fixed, learned, or built something. Imagine walking out with a body better then you went in with. Keep that in your head as you write down a list of what you will do every day at home—then get up and do it. Start early, before the excuses attack your resolve.

This doesn’t address the painful economic disasters many people face. To say there’s some vapid sports cliché—“When the going gets tough, the tough get going!â€â€”that will get you through, trivializes your pain. Push-ups and downward dog won’t pay the grocer. But they will help you cope with the stress by distracting you and preparing you for better days.

One of the most important lessons kids learn is about fair play.

Everyone is expected to play by the rules, with no one getting preferential treatment. Fair play in society is about treating all Americans equally, regardless of their income or celebrity. Yet, there is plenty of evidence that those with either or both those are getting preferential treatment. Singer Pink, who along with her 3-year-old son contracted coronavirus, addressed this issue frankly when she admitted that her celebrity allowed her to get tested before others. “I would say you should be angry that I can get a test and you can’t. But being angry at me is not gonna help anything. It’s not gonna solve the issue of the fact that you can’t get your hands on a test. You should be angry about that, and we should work together to try and change that.†While that may be a cause for outraged head-shaking in middle-class white neighborhoods, the lack of fair play is a death sentence for blacks, who suffer three times the infections and six times the number of deaths as whites. For example, Louisiana’s black population is 32 percent, yet they make up 70 percent of the coronavirus cases. This same disparity is true throughout most of the country. Ironically, one reason for this is that black Americans make up a higher percentage of the “essential services†workforce. African Americans are 50 percent more likely to work in healthcare and social services than whites. At the same time they are at higher risk, blacks also have lower access to health benefits. And all the synchroized applause and thanks-for-your-service isn’t making that fair play.

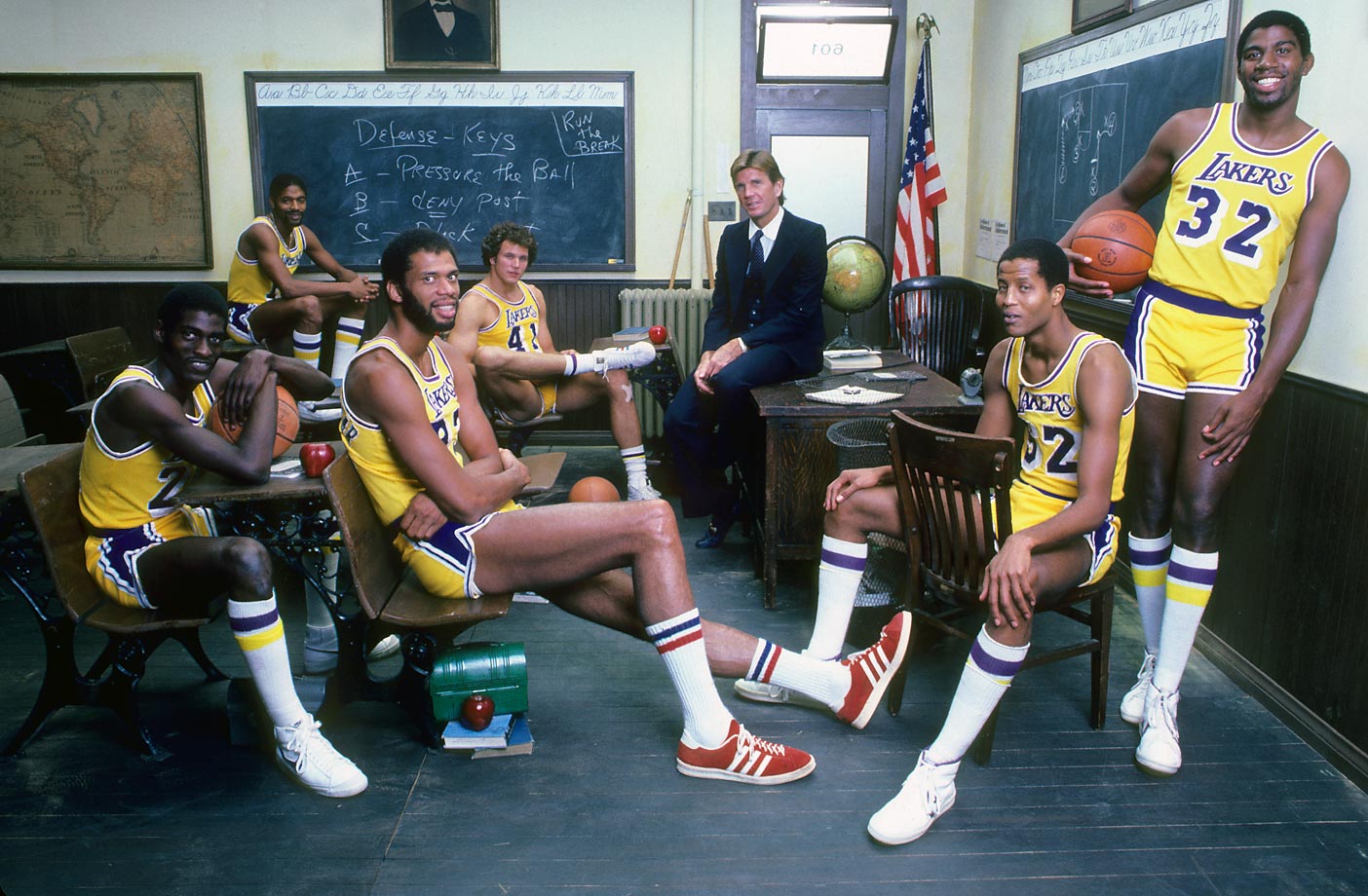

I’ve played on many championship teams and one of the most important determinants of our success as a team was having a great coach. Teamwork is only as good as the coach because the coach is in charge of selecting, training, and inspiring the team. The coach shows the team how to thrive as individuals while at the same time working together to succeed together. Unfortunately, America has a bad coach who places his own desire to be seen as a winner above that of his team actually winning. A good coach/leader always is honest with his team so they know what they are facing and can find ways to win. My teams have often defeated teams that appeared stronger, more experienced, more skilled because our coach was direct with us about their strengths and our weaknesses. Which only inspired us to find a way to beat them.

If Trump were a sports coach, his team would be the losingest team in history. Instead of coaching, he spends valuable time assuring the fans that they are close to turning it all around this losing season. With a few notable exceptions like Dr. Fauci (who had already been advising presidents since Ronald Reagan), he picks poor assistant coaches, which is why so many have quit, been fired, or indicted. When his coaching failures are pointed out, with facts and statistics, he blames everyone else: the mascot didn’t cheer enough, the hot dog vendors didn’t use enough mustard.

When a team has a bad coach, they replace them. Until that happens, the team learns how to work around the bad coaching by relying on each other. Because in the end, we’re the ones who have to take the floor or field and put our bodies on the line. And there is great comfort to looking over at your teammate who is hustling through the pain beside you.