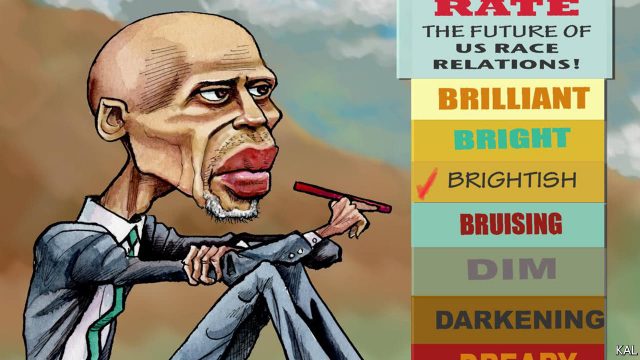

Lexington Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a brooding sportsman-sage

The former basketball player detects a bright moment for black activism

ADDRESSING the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in 2016, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar sounded uncharacteristically optimistic. “Those who think Americans scare easily enough to abandon our country’s ideals…underestimate our resolve,” said the former basketball player, betraying, as he stooped over the podium, his unconscious habit of trying to make his seven-feet, two-inch (2.18m) frame less conspicuous. Now hunched behind a table in his office in Los Angeles, Mr Abdul-Jabbar, who scored over 38,000 points in the National Basketball Association, a record never surpassed, says he enjoyed the experience. It was the first appearance at a party confab by anyone in his family since his father, a trombonist, accompanied Marilyn Monroe’s rendition of “Happy Birthday, Mr President” in 1962. He also cracked the convention’s best joke—introducing himself as “Michael Jordan”, on the basis that “Donald Trump couldn’t tell the difference.”

Yet Mr Abdul-Jabbar, who has probably written more books than any other basketballer, too, and is not known for his sunny outlook, was less confident in America’s moral purpose than he let on. “I always knew [Trump] had a strong chance to win because his appeal was to racism,” he says quietly. “People in America won’t admit they have racist feelings and will vote accordingly.” That is a sentiment more familiar from his writing, including a dozen books and hundreds of articles, many of which consider the persistence of racism in America. It is probably right, too. Since the election, many political scientists have suggested that racial resentment—defined by one scholar as a “moral feeling that blacks violate such traditional American values as individualism and self-reliance”—was a bigger factor in rallying white Americans to Mr Trump than economic anxiety. The promise of a post-racist society many saw in Barack Obama’s election looks far off.

Upgrade your inboxReceive our Daily Dispatch and Editor’s Picks newsletters.

As a child prodigy and pioneering black sportsman, Mr Abdul-Jabbar witnessed many cycles of racial progress and setback. Growing up in multicoloured Harlem as Lewis Alcindor, the son of a police officer and seamstress, he says he did not realise he was black until third grade. Yet he cites the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American lynched in Mississippi that same year, 1955, as having a profound influence on him. “I couldn’t understand it and my parents didn’t have the words to explain,” he says. His alma mater, the University of California, Los Angeles, which he entered in 1965 as a coveted teenage player—already over seven feet tall and the creator of an unstoppable shot, the skyhook—had integrated early. Yet Mr Abdul-Jabbar suffered all manner of racist slurs there. “There’s no way having people call you nigger every night doesn’t affect you,” he once wrote.

Within a year he was nationally famous and politically active. He was the youngest to attend a summit of black athletes in Cleveland, to support Muhammad Ali after the boxer refused the Vietnam draft. After the assassination in 1968 of Martin Luther King—whom Mr Abdul-Jabbar had interviewed as a schoolboy journalist—he refused to be considered for the Olympic games held that year, and converted to Islam. “The history of the Christian world with the slave trade was very seedy,” he explains.

This was a formidable sporting and civil-rights record; Mr Abdul-Jabbar was celebrated by neither activists nor sports followers with the ardour he deserved. He was not charismatic like Ali. He was introverted and difficult. He disliked journalists. Playing for the LA Lakers, his quiet fierceness was contrasted unfavourably with the sunniness of his teammate, Magic Johnson. Mr Abdul-Jabbar fretted that white Americans would misinterpret Mr Johnson’s bonhomie as a signal that the civil rights struggle was over. (“That was the effect, but I didn’t blame Magic for it. We were friends and respected each other.”) He was more critical of Mr Jordan, who was once said to have refused to campaign for a Democrat on the basis that “Republicans buy sneakers, too.” “It was because he wouldn’t engage politically,” says Mr Abdul-Jabbar. “I wasn’t trying to stick him up for anything, but just some support, an acknowledgment that we have issues that are important, and he wasn’t open to it.”

Yet in 2016 Mr Jordan pledged millions of dollars in donations to civil-rights groups. “He’s come around,” says Mr Abdul-Jabbar. This was in line with three trends that he credits with reinvigorating the political impact of black role models. First, the fact that the biggest stars have made billions of dollars; “there’s power there,” he says. Second, a general sense of disgust among black Americans at the Republican campaign to demonise Mr Obama, which Mr Abdul-Jabbar, like most black Americans, attributes to racism, and thinks probably laid the ground for Mr Trump. Third, the role of digital technology in broadcasting the daily injustices black Americans suffer, including the police atrocities that inspired Colin Kaepernick, an American football player, to kneel for the national anthem. “We all thought that was over—you know, Barack Obama was elected,” he says. “But it’s not over.”

A slam-dunk case

Mr Abdul-Jabbar seems revivified, too. Prominence on social media has introduced him to millions. He published two books in 2017, including a moving memoir of his friendship with his (white and pious Christian) coach at UCLA, “Coach Wooden and Me”. At 70, he might even have mellowed a bit. He says he feels more able to “understand the blind spots that affect white people.” America’s recent progress on race relations, he adds, has “in many ways surpassed my expectations”. By the basketballer’s brooding standard, this is such an upbeat note your columnist rashly ventures a cheerful last question. Does he still enjoy Christmas?

“No, I never liked it that much,” Mr Abdul-Jabbar says blankly, unfurling his long limbs to go. “It’s so commercial. The spirit of Christmas should be the Christ child.” He shakes his head. “It’s a disappointment.”