by Kyle Stack – Slam Online

One would think Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would forever be most closely associated with the NBA’s all-time scoring list, given that he’s atop it. Yet for his 38,000-plus points, six NBA titles, six NBA MVPs and three national titles at UCLA, his identity has grown beyond being just a basketball player. He’s become an historian of basketball, and of black history, for that matter.

One would think Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would forever be most closely associated with the NBA’s all-time scoring list, given that he’s atop it. Yet for his 38,000-plus points, six NBA titles, six NBA MVPs and three national titles at UCLA, his identity has grown beyond being just a basketball player. He’s become an historian of basketball, and of black history, for that matter.

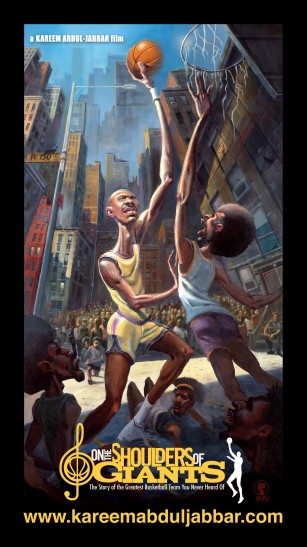

Abdul-Jabbar has written a series of books on black history through the years, with his latest coming in 2007, when he wrote On The Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance. The book detailed black culture in New York City in the first half of the 20th century, including an exploration of the Harlem Rens basketball team. Abdul-Jabbar’s interest in the squad, which compiled a 2,588-529 record from 1922-49 as the first all-black professional basketball team, is captured in the documentary version of On The Shoulders of Giants.

The feature-length documentary, co-written and co-narrated by Abdul-Jabbar, delves into the history of the Rens, the team’s impact as pioneers for blacks in basketball and the team’s role in early 20th century Harlem. It’s available on Video On Demand on Time Warner, Cox and Comcast cable networks nationwide through March 31. Abdul-Jabbar spoke with SLAM about the documentary and an assortment of NBA-related topics.

SLAM: What motivated you to document this subject?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Well, I really wanted to do the film all along. But because the subject is so unknown and unacknowledged, I had to do the book first, just so that I could have a document up there that depicted the story and what it was about. If you don’t have something like that, then people don’t really know what you’re talking about when you’re talking about a very overlooked subject.

SLAM: I spoke with Charles Barkley about this film — obviously, he makes an appearance it — and he admitted he hadn’t heard of the Rens before he was invited to be in this project. How many NBA players have you come in contact with who didn’t know of the Rens?

KAJ: You know, we’re talking about almost 100 percent. The Rens played at a time before the NBA started, and at a time when black Americans weren’t recognized for anything. The combination of those two circumstances — and the fact the NBA seems to everyone to be what basketball was all about starting in 1947…most people don’t even believe or have any idea that professional basketball was played before 1947, and who the greater teams were. So, I think the whole ignorance about anything prior to the advent of the NBA really has caused what you’re referring to.

SLAM: Parts of this film document the treatment endured by blacks in this country during the 1920s, ’30s and earlier, including lynching in different parts of the country. Did you become overwhelmed with emotion at any point during research for this? Did anything anger you?

KAJ: Well, you know, I was raised during the 1950s and 1960s, and what I saw during the Civil Rights Movement was enough, in too much detail, what that was all about. That is a very sad and unfortunate aspect of American history — how black Americans were treated for so long. I was aware of that, that no one escaped that type of treatment. I’ve been aware of that my whole life.

SLAM: Was there anything you learned through research in this project that you weren’t previously aware of?

KAJ: I guess, I didn’t realize how long the Rens had played before they got their shot. You know, like everyone else, not having any first-hand information about the Rens, I was in the dark. When I was in high school, I learned a little bit about them and that they were a very good team. And that was about it. I didn’t find out what they were all about in-depth until after I had played professional basketball.

SLAM: Since the Rens were extolled in the film as being one of the all-time great basketball teams, what do you think defines a team?

KAJ: I think a team is defined by their record. That is usually what defines any team, no matter what sport it is. The record is a lasting legacy of what they were all about.

SLAM: But with all your success at UCLA, with the Bucks and then the Lakers, did your idea of what it takes for a team to succeed change once you learned more about the Rens?

KAJ: Not really, because the Rens, like all the great teams, were winners. They had to overcome more obstacles than the average professional teams. The fact that blacks were excluded was a huge hurdle for them to overcome. But they loved the game, and they played a superb game against the best teams in the country, even though they were not given credit for being as excellent as they were. That was okay for them. It was obvious somebody was listing something because their outstanding record was there — they won over 2,000 games over a period starting in 1922 through 1948. An incredible record.

SLAM: What did you learn about New York City during this project that you didn’t previously know?

Dolly King was a player from LIU — he played for the Rens in the ’40s. In the 1940s, they normally played out of Washington, who were a championship team. And he officiated a lot of my high school games. I hadn’t known he played on the Rens. I had just known he had gone to LIU; I didn’t know much of what happened with him after that. So, a lot of these stories were very close to me.

The Renaissance Theatre [in Harlem, where the Rens played their games] — my dad used to go there when he was in high school. Again, someone in my family was aware of King. But there was no connection. He never really talked to me about it, and I just found out in the few years after I retired of his awareness of what the Rens were all about it.

SLAM: Yeah, and I think through the film your appreciation for where you grew up is reflected in it. You grew up in Washington Heights, right?

KAJ: Inwood, actually. Inwood is the next neighborhood north of Washington Heights. My neighborhood…it’s, like, two miles from Harlem. It’s very close to Harlem. And, you know, all of our friends, my family friends, still live in Harlem, so Harlem is still very close. But my family lived in Inwood.

SLAM: Growing up there, did you have an appreciation for your neighborhood and the surrounding areas?

KAJ: Well, I had a very strong appreciation for Harlem just because it was such a great place for black Americans. Even with all the negatives there — the negatives that were found in many black communities at that time. Harlem still was a place of great pride for black Americans. Because of that, it impacted me greatly in the things that I did and what I thought about.

SLAM: There are so many great people in this film — Spike Lee, Maya Angelou, Cornell West. How did you approach the folks whom you wanted to participate in it?

KAJ: Well, I was very lucky in that a lot of the people I asked to participate in the film were aware of who I was and what I was about. And they think of me as being more than just an athlete. They knew that I had a serious approach to this, that I’m near and near to black Americans and black history. They were aware of that. Fortunately for me, it was easy for me to approach them and to get their cooperation.

SLAM: Carmelo Anthony had a good role. I was surprised at the level of appreciation he showed for an earlier generation. What did you think of his involvement?

KAJ: I was very thankful that Carmelo took the time to give us some quotes like that. And like most young players now, they don’t know too much about the Rens and what had to happen for them to have the opportunity that they had. Once they are made aware of it, they are very appreciative and they’re very much willing to acknowledge and go public with their acknowledgment of what the Rens did and the debt that they are owed.

SLAM: Have you discussed black history much with this current generation of NBA players?

KAJ: Oh, I don’t have an opportunity to get to all of them. It’s really a hit-or-miss thing for me. When I meet some of them, and when I get the opportunity to talk about the subject, I do. That is something that sometimes happens and most often doesn’t happen.

SLAM: What do you want people to ultimately get out of this film, even for white people and folks of other races and ethnicities, who may not have ties to Harlem or New York City, in general?

KAJ: Well, I hope they get an idea of what had to happen for us to get to this point. And just the acknowledgment that the Rens get from people seeing and learning about them…that’s one of the great things made possible by me doing this documentary. People are becoming aware of it. For example, people were not aware of the fact that [former UCLA men’s basketball coach] John Wooden played professional basketball and often competed against the Rens when they came to Indiana. They often played Coach Wooden’s team; he played for a team in Indianapolis. He said to me, his team couldn’t beat the Rens. Coach Wooden was a fine professional basketball player.

SLAM: Had you discussed that with Coach Wooden through the years?

KAJ: Oh, when I first started doing documentaries, he was one of the first people I went to, to interview. I got some in-depth knowledge from him about what the Rens were about. He told me about how they played a really great passing game. They kept the ball moving the entire time. They kept their bodies moving, and it was a very difficult team to guard. They played a tight defense. Everybody one-on-one; everybody that was on the court kind of influenced Coach Wooden’s coaching schemes later on in his life. He knew effective ball movement would help a team become a dominant team.

SLAM: A final question on this topic. With your role in working on projects regarding black history, is this as big of a passion for you as basketball was when you played?

KAJ: Oh, definitely. I’m on the coaching staff for the Lakers, but this is becoming a very important aspect of my life. I have an opportunity now to do some more, and I’m looking forward to taking advantage of that opportunity and doing more things like that.

SLAM: On to some other topics. I’ve read about your time when you played for Milwaukee and why you wanted to play in New York or L.A. What were the circumstances around that trade from Milwaukee to the Lakers?

KAJ: Well, basically, Oscar Robertson had retired. He retired after the 1974 season. And things didn’t look good, in terms of any immediate…the Bucks did not have the talent to be contenders for a world championship title at that point, once we lost Oscar Robertson. So, I wanted to move on. I let the management people know I wanted to move on. My contract with them was going to be up after the 1976 season. So, they only had me on contract for one more year, at which point I would be a free agent. So, for them the best that they could do would be to trade me while I still had a year left on my contract. They could trade me and get what they needed to get to refurbish their team and get back into contention for a league title.

SLAM: That situation sounds similar if you look at Carmelo’s situation when he was in Denver. Is it fair for a player to determine where he wants to play next, even if it’s through a trade?

KAJ: Well, you know as long as the player lives up to the terms of his contract, as long as he plays hard and gives a good, honest effort every time he goes out there and lives up to the terms of his contract. When it comes time for him to have the opportunity to move on, or stay, that’s a business decision. Basketball, at that point, is a business.

I thought Carmelo handled it really well. He knew that he wanted to move on, and he never started dogging it, in terms of not living up to the terms of his contract with the Nuggets. He was at a point where he wanted to move on. It was a business decision to him; I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

SLAM: I’ve always identified you with the evolution of the NBA more than any other player, just for the fact that you came in the year after [Bill] Russell retired and you left right before [Michael] Jordan hit the height of his dominance. Do you ever reflect on your role in the NBA during its evolution from the ’70s and through the ’80s?

KAJ: Yeah, sometimes I do. It was a really interesting time because when I came into the NBA it was still more or less the NBA of the 1960s, and when I left the NBA, the NBA was going on to the ’90s to become a very popular and special professional sport. So, I saw a lot of change. I think starting with the ’79-’80 season the NBA really started to take on a big role in terms of public awareness. People really enjoyed the dominant teams of that era — the Celtics, 76ers, Lakers, San Antonio. There were a number of good teams. Seattle, the Bullets. There were a lot of really good teams. So, it was nice to see the NBA evolve and overcome its third-place status among the major sports in America.

SLAM: Have you witnessed any players try to emulate your skyhook during a practice or any other situation?

KAJ: You know, Magic asked me to show me how to shoot it, and I showed him. He was able to use it to a pretty good effect. There’s only one other players nowadays that kind of shoots it like I did — LaMarcus Aldridge. It’s a great shot. I don’t think too many players use it now because the coaches teaching kids today seem to be only teaching guard skills. They teach how to play facing the basket, shooting jump shots — the jump shot is the dominant shot now. It makes it kind of hard to get the knowledge to teach this generation about playing with your back to the basket and using a different array of weapons. That has to do with the evolution of the game. But human physiology hasn’t changed. It’s still a great shot if you’re going against somebody — especially if you’re going against somebody taller than you are. It’s a great shot to use.

SLAM: What do you remember about your time witnessing basketball games in Harlem?

KAJ: Well, I used to see the Rucker League, starting in the early ’60s. The big game every summer for the Rucker League was against the Baker League from Philadelphia. That was a special contest. But in Harlem, the Rucker summer tournament is very popular. I saw Wilt Chamberlain’s team, some of the teams that had great New York City urban legends — I watched them play. It was a lot of fun.

SLAM: I recently wrote a story for SLAMonline about NBA players and teams using yoga. You used yoga for most of your career — is that correct?

KAJ: Yes, basically starting about the time I got traded to the Lakers. I was going through the Bikram Yoga College of India — they call it hot yoga now. It was a good experience for me. I’d say my ability to retire when I wanted to retire had a lot to do with the fact that I incorporated yoga training into my regimen. It really helped me in a lot of ways.

SLAM: I couldn’t let you go without asking you about the NCAA Tournament and your time at UCLA. Is there a game in particular from the three tournaments you played in that stands out among others?

KAJ: Oh yeah, UCLA vs. Houston in 1968. We beat Houston in the Astrodome. By winning that game…Houston seemed to convince everybody in the country that they were the best team. And the UCLA Bruins had a totally different opinion on that subject, and we were anxious for an opportunity to show people what we were talking about. It all worked out very well. We played them in the semifinal and showed them who was the best team.

SLAM: Do you still keep a close association with UCLA?

KAJ: Um, yes and no. The university has asked me to do some public announcements, and I’ve done that for them. I don’t go to too many games; I am in contact with the guys that I played with. I do have some contact with the present regime and friends of the people in charge with the basketball program.

SLAM: I just want to leave you with a final question about On The Shoulders of Giants. Are there any other points you would like to make about this film and your role in it?

KAJ: I’m glad there is some interest now in knowing what the landscape was like back in the 1920s and ’30s. I hope people enjoy watching the documentary and hopefully some of them will take a peek in the books and see what was happening at that time. It’s very interesting stuff.