–Mark Medina, Los Angeles Times Lakers Blog

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart1a.flv 598 336]

It was a who’s who of basketball — former Laker Jerry West, former Celtics center Bill Russell, Chicago Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, former Harlem Globetrotter Marques Haynes among them — and amid their laughter, arguments and playful ribbing, it became apparent that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s question about what basketball team was the best in history was not going to be met with an easy consensus.

This scene didn’t come from a sports talk show, although it would’ve made for riveting television. It was from Abdul-Jabbar’s documentary, “On the Shoulders of Giants,” a 75-minute movie narrated by Jamie Foxx that focuses on the Harlem Rens (also known as the New York Renaissance) and the effect of that basketball team both on the sport and society.

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart1b.flv 598 336]

When Russell touted his 11 championship rings and claimed superiority over any former or modern NBA center, including the Captain himself, West immediately intervened and argued Abdul-Jabbar would’ve blocked Russell’s shots. When West brought up the Lakers’ five NBA titles in the Showtime Era during the 1980s, Reinsdorf argued that that accomplishment paled in comparison with the Bulls’ six NBA championships in the 1990s. And when Reinsdorf boasted that Scottie Pippen limited Magic Johnson in the 1991 NBA Finals, West then argued the outcome would’ve been different if Abdul-Jabbar hadn’t retired in 1989.

Shaking his head in amusement, Abdul-Jabbar told the panel they all were wrong, saying the Harlem Rens were the “greatest basketball team you never heard of” for plenty of reasons. They compiled a 2,588-529 record during their 27-year existence, from 1922 to 1949. The Rens played basketball with what Abdul-Jabbar described as a “no-nonsense approach” — quick passes, minimal dribbling, balanced scoring and “suffocating defense.” And most importantly, the all-black Rens team helped spur integration by playing exhibition games against all-white teams.

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart2.flv 598 336]

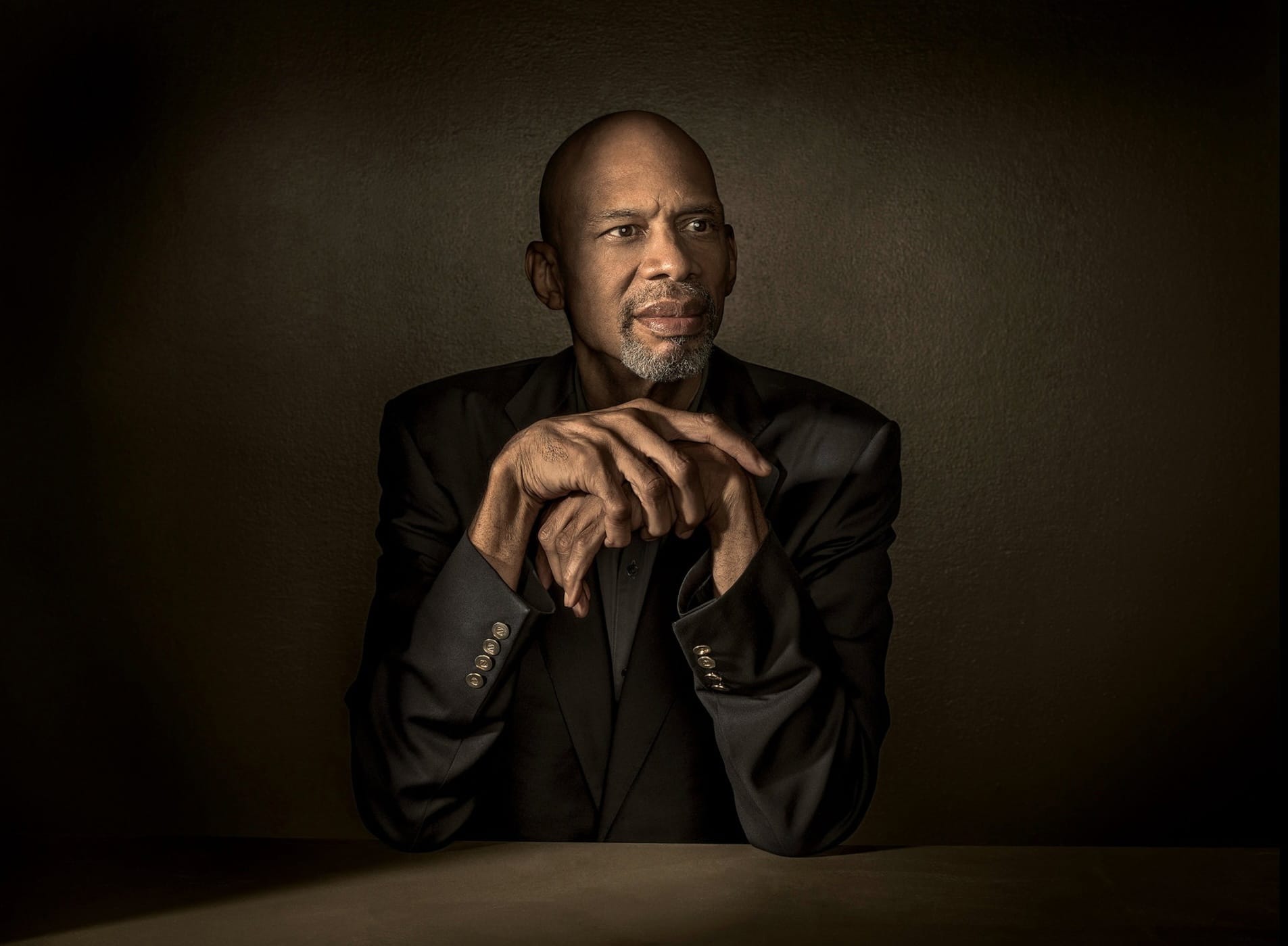

“It helps them understand how the game got to where it is today,” said Abdul-Jabbar of the film, which was featured in a screening Saturday at All Saints Church in Pasadena and can also be viewed on Netflix. Following the screening, Abdul-Jabbar and others who worked on the film — including director Deborah Morales (to Abdul-Jabbar’s right) and jazz great Bill Cunliffe (to Abdul-Jabbar’s left), who composed the score and writer Anna Waterhouse — sat for a question-and-answer session.

Abdul-Jabbar will be honored for his efforts on the film with a Lincoln Medal at the Ford’s Theatre Society annual gala on June 5. “All the things they didn’t understand what people had to go through to get this point where we have this wonderful game, make all this money and become famous, it wasn’t always like that, especially black Americans, who were kept out of the mainstream of American life. The Rens played so hard and showed the whole basketball-loving public the best athletes were not all playing in the established leagues. It helped change things.”

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart3.flv 598 336]

The Rens went 112-7 in the 1932, 1933 and 1939 seasons and finished with a 2,588-529 overall record. Abdul-Jabbar equated Harlam’s up-tempo style as just as revolutionary to basketball as Bill Walsh’s West Coast offense became to football. And they won the World Professional Basketball Tournament in Chicago by beating the Harlem Globetrotters and the all-white Oshkosh All-Stars in 1939, exactly eight years before Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and sparked racial integration in baseball.

The film showed how Harlem faced similar challenges in race relations. Owner Bob Douglas forged a deal with the Harlem Renaissance Casino and Ballroom that included calling his team the Renaissance so the casino would receive publicity. In turn, the Rens practiced and played home games at the ballroom, often immediately before and after dances. Harlem often played five to six nights a week, a stark contrast to the NBA’s current 82-game schedule. Road games were an exercise in crowd control, with those attending trying to distract players by throwing objects on the court and putting their feet out to trip them.

“Jackie Robinson played for America’s pastime,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “In the 1930s, basketball was not America’s pastime. Basketball was like for those watching the Olympics when they watch curling. It wasn’t the thing at the time.”

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart4.flv 598 336]

Soon enough, however, the Rens’ presence helped bring change. The Globetrotters, for one, featured an all-black team, although they focused on on-court theatrics rather than actual basketball. Former Ren Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton became the first black player to sign an NBA contract by joining the New York Knicks in 1950. And the white teams, most notably the Original Celtics, soon respected the Rens’ abilities.

Abdul-Jabbar said his documentary would have aired two years earlier, instead of on Feb.10, 2011, during All-Star weekend, had he been able to formulate the correct creative vision. Also, he admitted, he’s new to making documentaries, so the process, he said, was like “moving a glacier.” Obtaining footage of the team was difficult — the only footage of the Rens actually playing came in a 40-second clip that Abdul-Jabbar obtained from a rabbi in upstate New York that shows the team competing in the 1939 World Professional Basketball Tournament.

But Abdul-Jabbar made up for those shortcomings. The NBA’s all-time leading scorer lined up guests, including those closely involved with the Rens as well as notable figures such as West, Russell, David Stern, Charles Barkley, James Worthy, Carmelo Anthony, Bob Costas and the late John Wooden. The documentary compensates for lack of footage with myriad photographs and paintings. And musician Bill Cunliffe composed for the film various pieces of jazz music that fit the period.

“We had to fill everything else in as best we could,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “It really gave the film a great flavor.”

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart5.flv 598 336]

Abdul-Jabbar also revisited Harlem, where he grew up. He recalled falling in love with history as a junior high student. He fondly remembered asking the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. a question about the civil-rights movement. He waxed nostalgic about finding old arrowheads and musket balls as a child growing up in Harlem, presumed artifacts from the Revolutionary War.

At one point in the Q&A following Saturday’s screening, an audience member asked Abdul-Jabbar about the recent hubbub concerning the failure, so far, of the Lakers organization to erect a statue in his honor. He simply replied, “I’m in the Hall of Fame. Who cares about a statue?” Still, the controversy that cropped up after Abdul-Jabbar said that the organization had disrespected him hasn’t disappeared.

But the basketball great remains open to future projects of the filmmaking kind, though he’s in no rush right now.

“We’re trying to make the best of our 15 minutes of fame,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “As new filmmakers, it’s all new to me. It’s a great opportunity. But I don’t want to blow anything.”

[flv:https://kareemabduljabbar.com/flv/kajosgpart6.flv 598 336]