WORCESTER —  When retired basketball superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar bumped into his father’s good friend Leonard “Smitty†Smith in 1993 at a movie premiere about the 761st Tank Battalion, he learned something he’d never known: The former transit cop was a war hero.

Smitty was part of the all-black battalion that was pressed into service because of its members’ skills. Most black units in World War II were formed largely as public relations maneuvers and many black soldiers, including Mr. Abdul-Jabbar’s father, Al Alcindor, soon realized they’d never see combat, Mr. Abdul-Jabbar said.

But under Col. Paul Bates, the 761st trained hard, studied the German tanks that had been sent back to the United States and realized the limitations of their own artillery against the panzers.

“He did not see blacks as inferiors,†Mr. Abdul-Jabbar said of Col. Bates during a talk and book signing yesterday at The Hanover Theatre for the Performing Arts.

The program was part of the Harold N. Cotton Memorial Lecture series run by the Jewish Federation of Central Massachusetts. Cotton was a past president of the federation.

The federation’s executive director, Howard Borer, said that when Mr. Abdul-Jabbar’s book about the 761st, “Brothers in Arms,†landed on his desk he knew the NBA’s top scorer would be a perfect fit for the series. Smitty’s battalion had liberated many from concentration camps and later, when blacks were fighting for civil rights, Jewish lawyers did much of the necessary legal work.

The two groups fought adversity and their links, both through the 761st and later in the civil rights movement, bind them.

Writing the book was a “labor of love,†Mr. Abdul-Jabbar said yesterday, in part because it was about someone he knew and thought of as family. And it was important because there was misinformation about the unit, even in the documentary he had seen that day in 1993.

The 761st caught the eye of Gen. George Patton, and when the allies needed tank replacements, he called on them. While many troops were given days of rest after spending a long stretch in the field, the 761st fought for more than 180 days without a break.

“They were so well-trained and so effective,†Mr. Abdul-Jabbar said. “They were probably the best trained in the U.S. Army in tank warfare.â€

While most people know his name from his high-scoring days with the Los Angeles Lakers, Mr. Abdul-Jabbar ranked the writing of this book, one of six he’s penned, high on his list of accomplishments. He finished the book in 2004, one year before Smitty died.

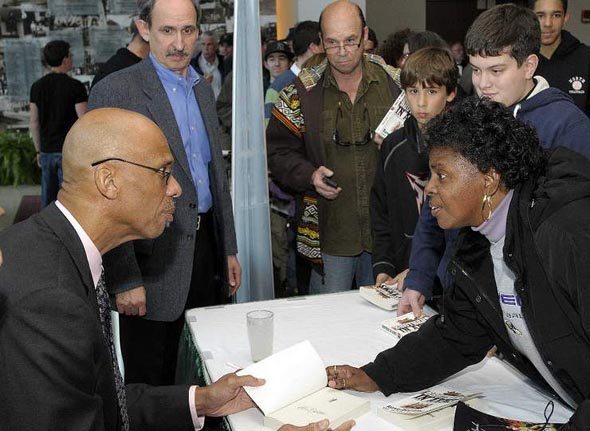

After the talk he answered questions about the book and his basketball career, telling one youngster that the reason his hook shot was so effective was “because it went in most of the time.â€

During the book signing, Kirsten Weindolt of West Boylston, a native of Denmark, braved the long line and when she arrived in front of Mr. Abdul-Jabbar, she pushed a folder of black-and-white 8-by-10 photographs toward him. On top, a picture of the Thad Jones and Mel Lewis Big Band showed young black men with afros holding trumpets, trombones and other instruments.

Mr. Abdul-Jabbar’s smile widened as he pointed out familiar faces.

Ms. Weindolt had worked as a photographer at The Village Vanguard, a New York jazz club.

“I hung up your coat once,†she told Mr. Abdul-Jabbar, and added that he could keep the photographs.

A convert to Islam, Mr. Abdul-Jabbar said in a quiet moment after the program that he hopes a planned Muslim community center not far from the World Trade Center site in New York City is built.

He said failing to build the center would delight those overseas who revel in seeing America divided.