by Barry Weintraub

The NBA’s all-time leading scorer has not stopped setting and achieving goals since retiring from basketball at age 42. In fact now, more than 20 years later, Abdul-Jabbar seems busy as ever. He is still a special assistant coach with the Los Angeles Lakers; an author; an advocate for children, cancer survivors and his Muslim faith; a public speaker; and a documentary filmmaker.

Abdul-Jabbar’s first film, due for release in February, is based on his 2007 book “On the Shoulder of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance.” It’s the story of the first all-black professional basketball team, the Harlem Rens, who played at the Harlem Renaissance Casino and Ballroom in the 1920s, usually as the opening act for some of the greatest jazz musicians of all time.

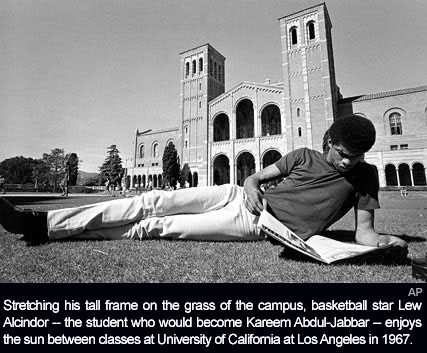

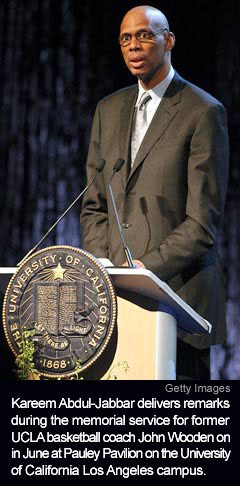

Many people over 40 will remember Abdul-Jabbar as the young Lew Alcindor, a 7-foot, 2-inch, basketball phenom from New York’s Power Memorial High School who moved West to win three NCAA championships under the tutelage of legendary college coach John Wooden at UCLA.

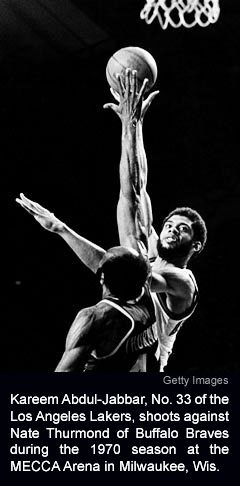

As a pro, Alcindor won his first championship with the Milwaukee Bucks in 1971, playing alongside the great Oscar Robertson. A few years earlier, he also drew attention and raised some eyebrows when he announced his conversion from Catholicism to Islam and changed his name. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would go on to win five more championships in a Los Angeles Lakers uniform before retiring with more than 38,000 points to his credit, six MVP awards and a host of other records and accolades far too numerous to recount.

Since retirement, Abdul-Jabbar, now 63, has remained close to basketball and was at times in the conversation for a number of head coaching jobs that never seemed to materialize. Nonetheless, he has been a special assistant coach with the Lakers since 2005 and has been instrumental in mentoring and working with the younger players who have melded with the veterans to win back to back championships over the past two seasons.

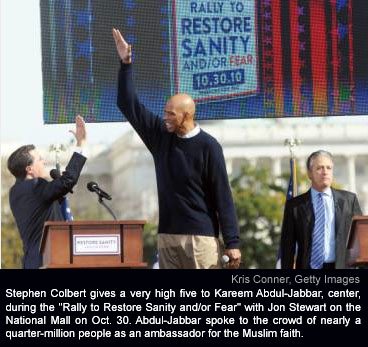

So it might have come as a surprise to many people when Abdul-Jabbar, known for his fierce competitiveness on the basketball court, appeared on stage in Washington, D.C., last month at the Jon Stewart-Stephen Colbert “Rally to Restore Sanity” before an estimated crowd of nearly a quarter-million people.

“It was nice to be a part of something like that where people are trying to figure something out and promote the right kind of values,” Abdul-Jabbar said of the experience. “The intent was pretty noble. I enjoyed being a part of it.”

His purpose on that sunny Saturday on the National Mall was to help make the point that the Muslim religion is one of peace and understanding. In the aftermath of 9/11 and more recently the controversy over the planned construction of a Muslim community center blocks away from the World Trade Center site, that message is seldom heard and often drowned out by the hatred, fear and misunderstanding of many who still equate Islam with the attack on America.

“The Islamic religion was not the motivation for 9/11”, Abdul-Jabbar says. “The motivation for 9/11 was the quest for power by people who are from Muslim countries that had become fascists, that’s basically what that’s all about. You know fascism has crossed many ideological lines, and people resort to it in terms of frustration or desperation or what have you? It’s like what was happening in Germany after World War I.

“The Islamic religion was not the motivation for 9/11”, Abdul-Jabbar says. “The motivation for 9/11 was the quest for power by people who are from Muslim countries that had become fascists, that’s basically what that’s all about. You know fascism has crossed many ideological lines, and people resort to it in terms of frustration or desperation or what have you? It’s like what was happening in Germany after World War I.

“It’s happening in countries that are majority Muslim, and they see the United States as the source of all evil and they convince people to believe in it. We know that that’s not true, but it’s hard for people to see that because of what’s going on over there in those countries.”

The Washington rally was not Abdul-Jabbar’s first effort to help promote tolerance and understanding. Earlier in October, he was the featured speaker at Hanover Theatre in Worcester, Mass., for the Harold N. Cotton Leadership Lecture sponsored by the Jewish Federation of Central Massachusetts. Abdul-Jabbar’s appearance was part of a concerted effort to reach out across ideological lines to help bridge the religious divide. And what was the message of this Muslim American to a largely Jewish audience?

“We’re all Americans. I’m an American. I believe in this country, and I don’t support in any way anything that people like Mr. bin Laden are all about. They are evil, there is no question about that. These people who are trying to gin up resentment against all Muslims are absolutely misguided or very cynical. People who are doing it to serve a political end or a financial end. … We don’t need that. We need some sane communication between all segments of American society.”

That message was very well-received, Abdul-Jabbar said, crediting in some part the story he told about one of his father’s best friends:

“A guy … he was a transit officer with my dad, I’ve known him since I was a kid. … He was involved in the liberation of several Nazi death camps where many Jews died, the most prominent being Dachau. His tank literally was one of the first tanks through the gates at Dachau, and it surprises many people that black Americans were involved in that effort.”

Abdul-Jabbar documented that story of the U.S. Army’s 761st Tank battalion in his 2004 book “Brothers in Arms.” It has since become an effective tool in his efforts to promote tolerance and understanding between American Jews and Muslims. But what about skeptical and outright hostile Muslims abroad? Has Abdul-Jabbar ever considered enlisting the assistance of other American Muslims to take that message to Indonesia or the Middle East?

“I haven’t had that opportunity,” he said. “I haven’t seen an opportunity to do that. I think it’s very difficult, particularly in the Middle East, not so much Indonesia, where you have governments that really aren’t democratically elected, governments that represent the will of the people or the system of rules and most countries with Muslim majorities are mostly autocratic. You know it’s a whole different atmosphere over here.

“I haven’t had that opportunity,” he said. “I haven’t seen an opportunity to do that. I think it’s very difficult, particularly in the Middle East, not so much Indonesia, where you have governments that really aren’t democratically elected, governments that represent the will of the people or the system of rules and most countries with Muslim majorities are mostly autocratic. You know it’s a whole different atmosphere over here.

“That’s why so many Muslims enjoy being American citizens. They can worship as they wish and criticize anyone they want to criticize. That’s one of the great things … that’s one of the things that makes America the great place that it is.”

Of course the right to criticize belongs to everyone, and many have chosen to exercise that right in response to the announcement in August of plans to build a Muslim community center a few blocks away from the former World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan.

Abdul-Jabbar, too, has very definitive views on this one: “You know I don’t get what the issue is? Some people want to portray this like a victory mosque, where Muslims are putting this up because they’re celebrating what happened on 9/11? I mean that’s absolutely a fabrication. It’s not true.”

Yet despite the existence of several other mosques in the area, not to mention the strip clubs that still reside just across the street, this community center has stirred protests and debate and was even an issue in the recent midterm national election. So what is the take of this native New Yorker and prominent American Muslim?

“I was really appalled at the way people wanted to view it,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “On Sept. 9, there was an article in The New York Times about a Muslim woman whose husband worked in the World Trade Center and was killed along with everybody else. They found his wallet but they never found his body. They found his wallet intact. He went to work on 9/11 and never came home. She wants to go down to the site and pray just like other religious folks and pray for the loved one that was murdered that day and you know with all this alarm and suspicion and hostility … you know, because, she’s Muslim.” His voice trailed off but the implication was clear. The woman is intimidated.

Abdul-Jabbar continued, “There were at least 70 American Muslims that were killed in the 9/11 attack, and you know there’s no consideration for them, and I haven’t seen any acknowledgment of them as it is. It’s only been from other Muslims. American Muslims were part, or were victims, of the 9/11 attack.”

Obviously, these are not easy times for American Muslims. There are many who view that community with fear and suspicion. So I asked Abdul-Jabbar how it made him feel when he sees the president being accused of being a Muslim, as if, if it were true, that would somehow make him un-American? This, too, is a question the basketball legend has given thought to.

“It really bothers me. It bothers me because what they’re saying is that because President Obama’s father is Muslim, somehow it makes President Obama sympathetic to the people who did 9/11. And no American is sympathetic to those people. They were murderers. That’s the only way you can describe them.”

Has Abdul-Jabbar ever encountered that kind of hate and suspicion? He says no. Might that be because he’s 7-foot-2?

“It might be? Or it might just be I don’t get lumped in with that? I’ve never been one to advocate any type of Islamic radical thought. I understand, you know the Islamic tradition teaches us that if you are a minority in a country and that country respects your religious beliefs, that’s your country. Pay your taxes and respect its laws and traditions, fight for it in the Army if you have to — that’s the Islamic teachings for Muslims when you are the minority in a country.”

Abdul-Jabbar’s passion for spreading tolerance and understanding at this time is more compelling when his own personal battle with leukemia is taken into account. First diagnosed in December 2008, Abdul-Jabbar went public with the news a year ago and has made awareness of the disease and fundraising for a cure yet another of his many pursuits. His son, Amir, was a medical student when Abdul-Jabbar first learned of his illness, which he reports is in total remission right now, where he hopes to keep it.

Amir was a great source of strength and guidance in those early days for his father. Asked if this gave him naches, before I could even finish my explanation of the term — a Yiddish term that means the great pride a parent feels for a child — Abdul-Jabbar cut me off and said, “Oh absolutely!” and then related a story about his own dad.

“You know, it’s funny, my dad, growing up during the Depression, he delivered ice. He was just 10 — maybe 10, 12 years old — delivering ice in Brooklyn and ended up carrying a lot to people who spoke a lot of Yiddish. And my dad, he spoke some Yiddish. He knew the language pretty well, you know, on a daily basis — to talk with the people in the shop — so my dad would have known what you were talking about.”

Abdul-Jabbar’s father was also a musician and contributed to Kareem’s great love of jazz. In many ways, his documentary about the Rens is also a documentary on some of the great jazz musicians of the ’20s and ’30s.

“The Harlem Rens is the greatest team you never heard of,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “They were the very first professional champions of basketball in America, and their home court was the Harlem Renaissance Casino and Ballroom in Harlem, which was a jazz venue. People like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington and Georgia Henderson and people like that played at the Renaissance. So I wrote about it, and I have a documentary coming out in February that tells their story and gives you some background on what that was all about.”

The Harlem Renaissance Casino and Ballroom was on 137th Street and Seventh Avenue. The Rens, who played mostly road games while compiling a 2588-539 record over its history, would play their games, then the baskets would be taken down and there would be live jazz until 3 in the morning. Abdul-Jabbar said he was able to find one piece of footage featuring the Rens playing ball and was fortunate enough to incorporate it into the film.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is clearly a very busy and motivated man. He still coaches with the Lakers and sponsors the Sky Hook foundation to “empower kids through sports.” He is an author, film producer, public speaker, cancer survivor and tireless activist for the promotion of tolerance and understanding. So does he ever get the chance to just veg out on the couch or go see a movie?

“Jeez, I don’t know. I love to swim in the ocean, and the Caribbean is my favorite place to go, and I did get my week to 10 days to get down to the Caribbean and swim and try to regain my tan. I did take a little time to do that, but I’ve been very busy.”

He also remains incredibly optimistic despite our troubled times. To what does Abdul-Jabbar attribute his high hopes for the future?

“I know that America, if there’s any hope in the world, to a large degree it’s going to start here. That people’s dreams still have a chance of coming true. So there’s going to be a better world. Americans are going to have something to do with it, and as Americans we need to think about how we can contribute to that.”