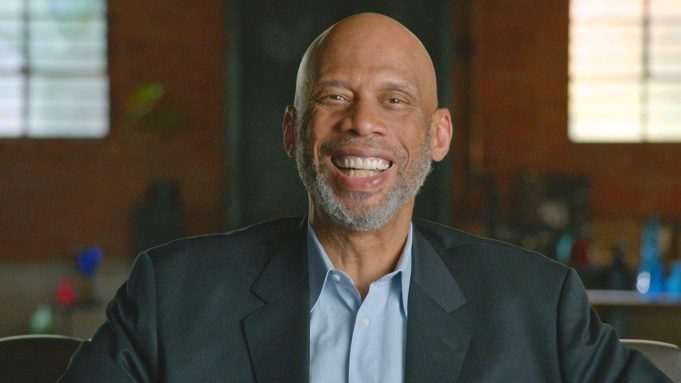

The NBA Hall of Famer and Hollywood Reporter columnist looks back at his career on the heels of the NBA’s creation of the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion Award, which will honor one player annually.

“I have often said that I will truly have achieved my full legacy when I have helped or inspired people who never knew I was an athlete. That will mean that I was able to use my fame from sports to improve the lives of people who never heard of me, never saw me slamdunk. I will have defined myself as someone more than the guy with the skyhook. Of course, I didn’t first pick up a basketball with the thoughts of creating a legacy. I just wanted to prove myself by beating the next guy or team who stepped onto the court. My court.

In high school, I was able to achieve my young boy’s goal of “proving myself” by defeating all comers on the court and on the playground. I had the trophies and college scholarship offers to prove it. At UCLA, things changed. Under Coach John Wooden, I was able to perfect my basketball skills to become part of a championship team. But my definition of “proving myself” evolved into something different. Coach Wooden wanted us to be great athletes, sure, but he also wanted us to be good people. To him that meant having high moral character as well as a well-rounded education because he was as concerned about what we would do when we left his tutelage as he was about what we did on the court. Basketball was a means to an end, not the end itself. Like any other college course, it prepared you — through discipline, hard work, and introspection — for life beyond school.

For Coach Wooden, part of being great athletes was to focus less on winning and more on pushing ourselves to perform at the top of our capabilities. Instead of “proving myself” to others, I learned to prove myself to myself by constantly pushing the limits of what I thought I was able to do. Yes, I wanted to please the crowds, excite the fans, win pennants, but mostly I wanted to do better in the next game than I had done in the last. To discover where my limit was. Like an explorer forging a roiling river in search of its source.

Athletes are entertainers. Like writers, actors, dancers, and musicians we get paid to thrill the audience. But there is a shimmering threshold that some cross over that transforms them from entertainers to artists: when they are able to not merely delight the audience, but also stir something dormant deep within them. It is when the artist becomes a tuning fork that triggers a similar tonal frequency within another person inspiring them to also try harder to reach whatever potential is inside. When they think: If that person can do that — make an impossible shot, write an elegant phrase, sing a haunting tune — maybe I’m also capable of more.

I realized it was gratifying to be able to inspire others as an athlete, but I also realized that wasn’t enough. If I pushed myself to become the best basketball player I could be, I should also push myself to become the best person I could be. That epiphany came when I was a sophomore at UCLA and NFL legend Jim Brown asked me to join the Cleveland Summit, a group of Black athletes meeting to decide whether to denounce or defend Muhammad Ali’s refusal to register with Selective Service because he claimed he was a conscientious objector. I was only 20, the youngest member of the group, and nervous that maybe I hadn’t yet paid my dues enough to be part of this accomplished gathering.

We debated heatedly. Some were military veterans and questioned Ali’s sincerity. But after hours of questioning Ali, we were all convinced. Ali would be stripped of his heavyweight title, banned from boxing which would cost him millions, face years in prison, and become hated among millions of white people as a draft dodger. The government even offered him a deal that would allow him to keep everything and he wouldn’t have to fight in Vietnam. He refused. His commitment was unbendable and we admired at his self-sacrifice.

The next year I boycotted the 1968 Olympics, not wanting to represent a country that was actively suppressing Black people’s civil rights, while beating, imprisoning, and killing those who fought for them. Dr. King had just been killed and I wasn’t in a particularly patriotic mood. Avery Brundage was The Olympic Commissioner. He had stopped Jewish athletes from competing in the ’36 Olympics so as not to offend Hitler. That was the origin story of my life as an athlete-activist — when I realized I didn’t want my legacy to be just a bunch of sports statistics that fans would argue about over beer and nuts. Oh, I still wanted to achieve those stats by setting records, but I also wanted to change lives.

While still in the NBA I started writing books that celebrated Black people in history who had made a huge impact on our country, but whom I’d never heard about in school. The attempt to literally whitewash history as if Black people had never done anything but be slaves and riot perpetuated the belief in generation after generation of white and Black children that Black people were of no worth. Even after retiring from the NBA, I continued to write books, articles, and documentaries extolling the achievements of inventors, scientists, patriots, writers, artists, and other Black people in order to educate Americans on their true history, and to inspire Black children to see they had many more career options than they realized. The further that goal even more, I started the Skyhook Foundation to promote STEM education among inner-city kids in Los Angeles.

During my 50 years as an activist, I’ve always heard the same complaint from some whites: Just be patient. Things are getting better all the time. True, but it’s not real progress just because you’re getting beaten with a smaller stick. People who aren’t marginalized are giddy about the progress because it makes them feel better: look, things aren’t as bad as they were. They see the glass as half full. But Black people see it as half empty knowing that the first half was probably drunk by someone white before the glass was passed down to us. What we see in that half-empty murky glass is the Black man choked to death while going to the convenience store, the Black woman shot to death while in her apartment, the Black 13-year-old shot to death with his hands in the air. That water tastes bitter.

By the way, that glass of water is more than a metaphor. Several reports over the last few years have concluded that in America there is unequal access to safe drinking water based on race. So, even if it is half full, what’s it full of?

My answer to people who ask why I’m still an activist when I could just be resting on my laurels as an athlete is that the work is not done. We’re being murdered in the streets and in our homes. States across the country are trying to suppress our access to voting. How could I not be an activist for my community?

Athletes have a unique standing in society. Unlike some other instant social media or reality TV celebrities, athletes have earned their fame through years of dedication, discipline, physical injuries, and failures. They are role models for perseverance and fair play. To not extend this opportunity as a role model to help improve the world seems like a betrayal of the values of athletics. But there are different types of activism: some are public, some are private, some are national or even international in scope, others are more community based. Each athlete must find what they are comfortable with and pursue that. For some, the type of activism evolves, as it did with me. Which is why over the years my participation with diverse groups dedicated to equity increased. I started with civil rights for Blacks and expanded to include immigrants, different religions and ethnic origins, LGBTQ+, etc., embracing Dr. King’s belief, “No one is free until everyone is free.”

The past few years have seen more and more athletes speak out and that has prompted sports leagues to join them in seeking social justice. As a result, the NBA has created the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion award to honor those NBA players who have made the pursuit of social justice a major priority. I can’t help but admire the NBA’s courage and long-term commitment to the cause of equity for all people. More than just joining the bandwagon they have chosen to be leaders. I am confident that this award will bring more satisfaction to the recipients than any records they break, any championships they win. Having my name associated with the award and with all the good that will be recognized because of it means my legacy has been fulfilled.

And I have finally proven myself to myself.”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is an American icon, legendary NBA champion and recipient of the 2016 Presidential Medal of Freedom. He is currently producing a series for The History Channel; the next episode, “Fight the Power: The Movements that Changes America,” airs on Juneteenth. On April 23, 2021, the NBA announced the creation of the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion Award, a new annual honor that will recognize a current NBA player for pursuing social justice named after Abdul-Jabbar, who has dedicated his life to the fight for equality