For marginalized groups — in the industry and at home — recognition by the Academy is more than an ego boost or a glamorous diversion but signals to the world that “the lives they live, the struggles they face, are worthy of depicting.”

The Oscar competition means different things to different people. For the average moviegoer, it’s mostly about the glitz, glamour and gossip. Nothing wrong with that. I’d like to know if Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield got along on the set of Judas and the Black Messiah. Did Leslie Odom Jr. give Aldis Hodge an atomic wedgie for drinking the last cappuccino at the wrap party for One Night in Miami? Gimme the tea!

For people in the film industry, the Oscars are about career boosts, artistic validation and financial rewards. “An Oscar really is life-changing for anyone involved,” said film financier Paul Brett, who won an Oscar as executive producer of The King’s Speech in 2011. “It opens enormous doors — every agent and producer wants to talk to you afterwards.” A director’s film that was in development limbo suddenly gets a green light, a writer moves from a $15 million film to a $100 million film, and an actor is co-starring with Meryl Streep instead of Tommy Wiseau.

But for most marginalized people — both in the movie business and in the movie theaters or at home in front of the TV — the Oscars represent something entirely different. It is a means to an end: having their stories told and being portrayed in ways that show the country values them as individuals and values their culture. Their worth can’t be established just by plugging in a Black, Asian, Latinx or LGBTQ+ sidekick character here and there, it has to come from the stories themselves in acknowledging that the lives they live, the struggles they face, are worthy of depicting.

Pop culture is the roiling language of the zeitgeist. If you want to know what society is thinking and what direction it’s heading socially, politically and morally, examine pop culture’s vibrant entrails. Movies form a large part of that pattern, which is why they are so influential in the culture rejecting and embracing ideas, ideals and people. Fiction is the architect of our future, and film has a long history of imagining a speculative world that the real world then makes happen. Whether it’s moon landings in A Trip to the Moon (1902) and From the Earth to the Moon (1958) or a Black president in Rufus Jones for President (1933) and 24 (2001), it happened on film before it became a reality. Film utters the childish possibility, which matures into the articulated reality.

That’s what movies and TV can do for marginalized people — erode the myths and misconceptions that keep them outside the mainstream by conveniently ignoring their contributions. The Oscar nominations announce to billions around the world which stories and storytellers matter. So every time a film is recognized by the Academy, the people represented by that film are also recognized. They become visible.

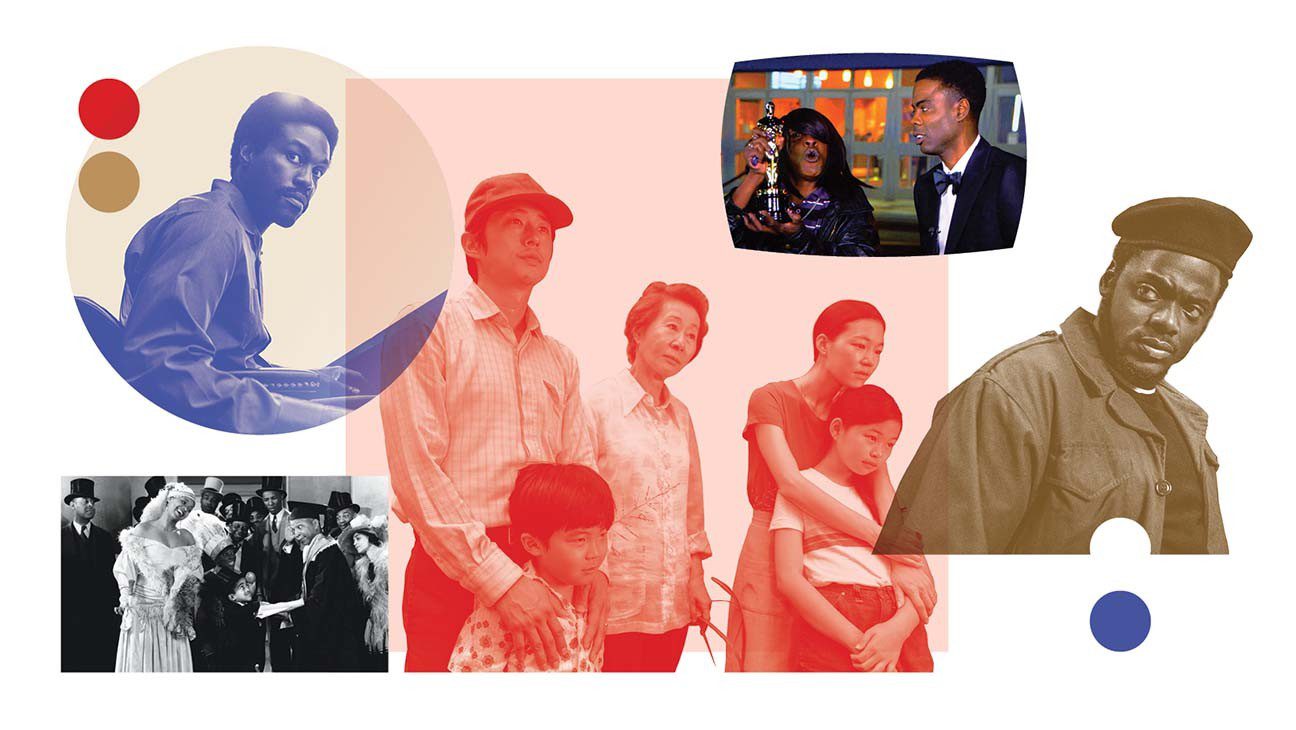

This was a good year for cultural diversity and the Oscars. Best picture nominations include major Black activist characters (Judas and the Black Messiah, The Trial of the Chicago 7), Asian American characters (Minari) and women (Nomadland, Promising Young Woman). Two of the five director nominees are women. All the major categories, including acting and writing, boast a balance of diverse voices. Even more important, these selections weren’t about virtue-pandering, they are all wonderful films that deserve praise. Two of the best films of the year are shorts. The Letter Room, written and directed by Elvira Lind, is a touching and hopeful film about the power of art to ease our isolation. Two Distant Strangers, written by Travon Free and directed by Free and Martin Desmond Roe, is a Groundhog Day-like meditation on the police versus Black community told with exceptional humor and horror.

This year, the Oscars got it right. The nominees are a choir of diverse voices — a song that celebrates the soul of who we want to be. Many underrepresented people are rejoicing.

But I wonder if this year’s diversity bonanza is because the theaters were closed and streamers became the great equalizer among viewers. Were audiences that had been previously ignored when theaters were open now welcomed into the fold because they were watching first-run movies on TV? While most people in the film industry receive DVDs or links to watch movies, Academy members are probably also more aware of the general public and movies that might reflect them and their viewing preferences. Especially after a year with a pandemic that almost destroyed the movie theater business and a year that included Black Lives Matter protests involving up to 26 million people. No one wanted to see a repeat of the tone-deaf 2016 Oscars that Chris Rock hosted during the #OscarsSoWhite controversy. In a famous clip, Rock interviewed mostly Black people outside a Compton movie theater, asking them about that year’s nominees. After asking if they’d seen Spotlight or Bridge of Spies, one woman asked if Rock was making up the titles because she’d never heard of them. This sentiment was echoed by several others. Though it was funny, it was also one of the most insightful commentaries on the power of movies to isolate people.

That’s why it’s important to know if this year’s Oscars are a pandemic anomaly or a sign that we are walking up the yellow brick road toward the future with arms linked and optimism that the members of the Academy really do have a brain, a heart, and courage.”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, an NBA Hall of Famer and the league’s all-time leading scorer, is a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom and a columnist for The Hollywood Reporter. Follow him @KAJ33 or visit kareemabduljabbar.com