With the disgraced star’s second trial underway, THR’s columnist admits he can’t watch his former friend’s shows “without anger, guilt or shame” as he confronts what offenses are “great enough to condemn the art along with the artist.”

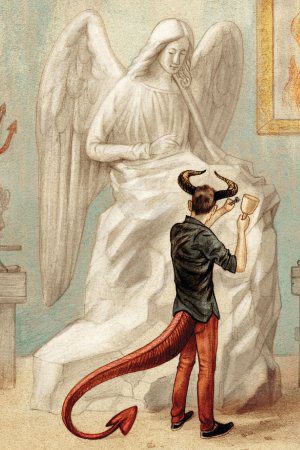

Since the Oct. 5 New York Times article detailing the atrocities of Harvey Weinstein, a growing tsunami of outrage has washed through American culture. From celebrities Matt Lauer, Kevin Spacey and Charlie Rose to political powerhouses Trent Franks, Roy Moore and President Trump, the list of infamy grows daily. But when that list includes names of beloved artists associated with social progress, such as Bill Cosby, Sherman Alexie and Al Franken, we are shaken on an even deeper level. Our initial anger and sense of betrayal makes us want to purge their artistic footprints from our cultural identity, and we are forced to ponder: What do we do with good art from bad people?

On her Hulu show, I Love You, America, Sarah Silverman, in response to the accusations of sexual harassment against close friend Louis C.K., posed the question, “Can you love someone who did bad things?” Most people eventually have to come to some decision about that question in their personal lives. But when the offense is widely known and the offender famous, we struggle with that question in a public forum that doesn’t allow much room for nuance or forgiveness. Instead, as Silverman said, “Some of our heroes will be taken down, and we will discover bad things about people we like or, in some cases, people we love.” Despite our personal feelings, we must paint them with the scarlet letter for the good of the community.

In the aftermath of this public outcry, positive changes have blossomed, from more female-centric stories in entertainment to formalizing sexual harassment regulations to a general awareness of what we as a society have been doing wrong and how to stop doing it. But along with those overdue gains, American culture has had some serious losses.

In 1965, when I was 18 and a senior in high school, I was struggling to find my identity as an African-American during one of the most tumultuous times in U.S. history. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been passed to violent protests, three civil rights workers registering voters in Mississippi were murdered, race riots swept the country, and I had just been called the N-word by my high school basketball coach. I felt not just marginalized in this country I grew up in, but actively hated. I saw a glimmer of hope appear in mainstream American culture when the 1965 fall TV season brought a new NBC show called I Spy, featuring a couple of buddy spies: one white, one black. Black? Never before had there been a black person in a starring role on a TV drama.

The black spy was played by comedian Bill Cosby. Improbably, he portrayed the smart one: a Rhodes Scholar who spoke numerous languages, knew all kinds of science and was an expert in fine arts and martial arts. I was buoyed watching him week after week, knowing that many Americans were seeing all blacks with more respect. The show was popular, and Cosby went on to receive three Emmys as outstanding lead actor in a drama series. His response to winning was defiant and exhilarating: “Let the message be known to bigots and racists that they don’t count!”

When I moved to Los Angeles to play basketball for UCLA, Cosby was my friend and mentor. I ate at his home, listened intently to his advice, discussed racial politics and laughed with him over small things. The accusations by 59 women that he drugged, groped and/or raped them was a punch in America’s collective gut. Yet, it was even harder for African-Americans because for 50 years, Cosby had been our totem to white America that we were just like you. Now that friendly, fatherly face had morphed into that of a sexual predator, and we had to share his shame for having paraded him around so proudly.

His fall from grace was America’s fall from innocence. But was I that innocent? Were any of us? Because, even though we find his actions despicable, we have to recognize that most men — and many women — colluded to maintain a social order corrupted by gender disparity. That disparity made women afraid to speak out whenever they were harassed. Every joke ever told about female drivers or ditzy blondes or man-eating businesswomen weighed them down in the eyes of society and made them afraid to speak out. We made Cosby and Weinstein possible by creating the environment in which they could thrive.

I’m confident that almost every male over the age of 20 can remember at least one incident from his past in which he made an inappropriate joke designed to embarrass a woman, an aggressive move meant to intimidate a woman or a physical insistence disguised as seduction. If you don’t think you have, you’re probably lying to yourself and have learned nothing from the society-altering #MeToo and Time’s Up movements.

I Spy, which ran from 1965-68.”>

I Spy, which ran from 1965-68.”>

I Spy and the even more popular Cosby Show have been exiled to a cultural Phantom Zone where we are in the process of sentencing the artworks of offenders deemed unworthy. But what we’re all wrestling with is what constitutes an offense great enough to condemn the art along with the artist. And how should we judge whether an accused person is really guilty or the victim of a vendetta or a sincere misunderstanding? Jennifer Lawrence articulated all of our struggles when she responded to a question asking if she would talk to accused sexual harasser Ryan Seacrest on the red carpet at the Oscars: “I don’t know. I think it is scary, you know. He has not been to trial for anything. I am not a judge. I am not a jury … that is where this stuff gets tricky.”

It is scary and tricky because shunning art for the actions of the artist opens a door to the kind of malevolent censorship that undermines democracy. We might soon include unpopular political positions, religious beliefs and social opinions. And what about art from accused people who deny wrongdoing and the evidence is inconclusive? Or collaborative art that supports numerous innocent people? We’ve come to some sort of social consensus that for the most part accepts the transgressions of dead artists — maybe because of a lack of urgency or laziness or because if we banned every sexist male artist, we’d have few men in our artistic canon.

The attempt to punish the art for the sins of the artist is not a one-size-fits-all remedy to bad behavior. Other factors have to be considered, including cultural and historic context and whether the art form is collaborative. Right now, we have dysfunctional and inconsistent criteria for punishing perceived wrongdoers — and for determining who they are. Jay Asher, the author of the novel Thirteen Reasons Why, and James Dashner, the author of the Maze Runner novel series, have been accused of sexual harassment and have faced harsh backlash. Should we also not go to the movies based on those books, even though that choice damages all the people whose livelihood depends on those movies?

What should we do? We definitely cannot rely on good intentions or the kindness of strangers. History confirms that every step of progress in a social movement is eventually met with a backlash to erode those gains. To prevent that, firm rules and definitions regarding sexual harassment must be in place in private business and government. Free legal aid must be available to accusers. Internal investigations must be conducted in a way that protects the privacy of the accuser and accused. More important, we have to continue to raise awareness, especially among our children, about what is appropriate and respectful behavior.

I can no longer watch I Spy without anger, guilt and shame. There are other shows, movies, books, artworks, comedians and musicians I can no longer enjoy. In addition to the horrendous devastation to the individual women, we as a culture are severely damaged, afraid to embrace any art or artist lest they eventually be tainted by bad behavior. We are all trapped in this necessary but exhausting j’accuse cycle of condemnation and punishment, denouncing and renouncing.

Yes, it must be done. Injustices must be identified as a mandatory step in eliminating them. What makes those who speak out about abuse — whether women, people of color, Muslims, immigrants or others — so heroic is that the act of speaking out traps the accuser with the accused. It reminds me of the closing lines of The Line-Up, a poignant poem by Joan Swift in which a woman at a police lineup to identify her attacker ponders the double assault of the crime and being the accuser:

The walls come in. I am

captured like him

locked in this world forever

unable to say run

be free

I love you

having to accuse

and accuse.

Read more at The Hollywood Reporter.