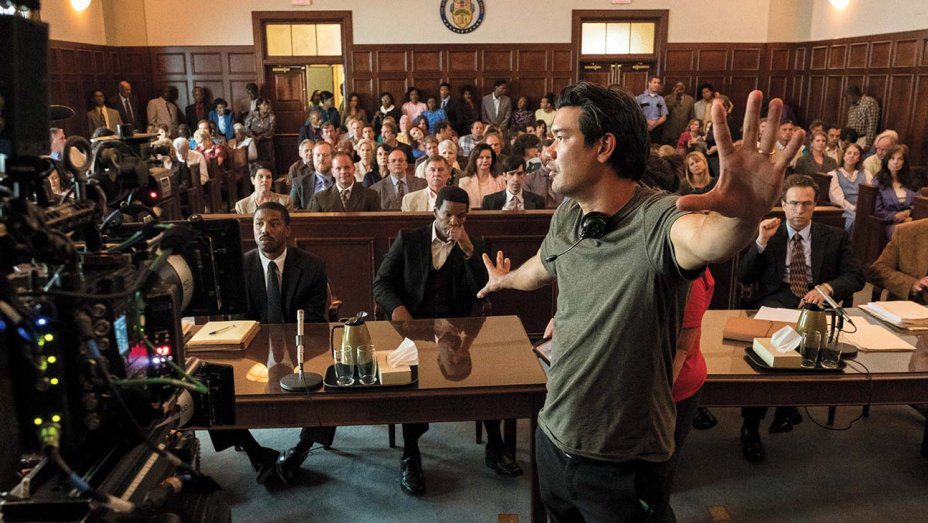

‘Just Mercy’ director Destin Daniel Cretton on the set of the Warner Bros. drama about lawyer Bryan Stevenson.

Movies about racial injustice can “exonerate us” when set in the past, but the evils are more urgent than ever, writes The Hollywood Reporter columnist.

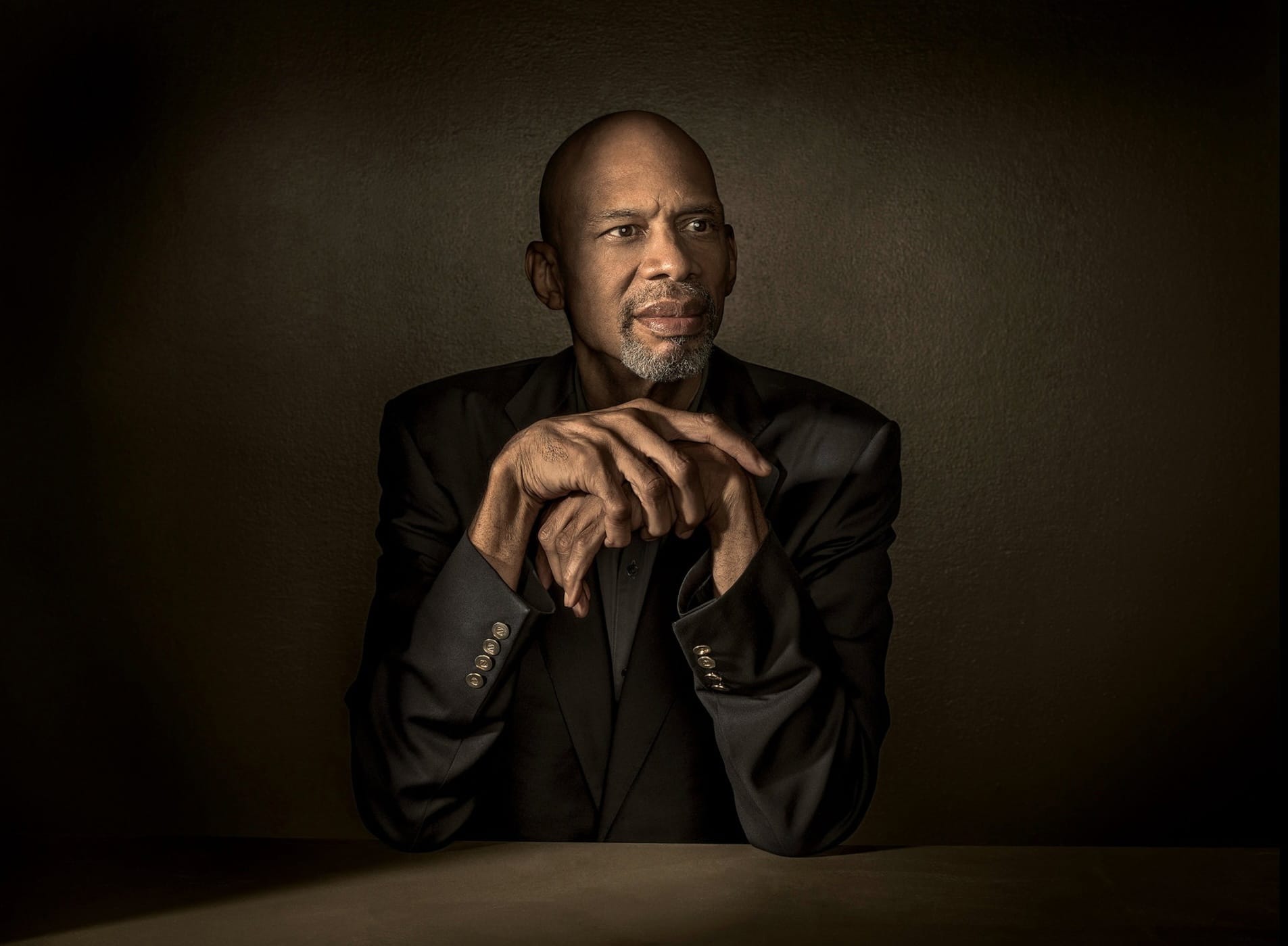

In Just Mercy, when attorney Bryan Stevenson (Michael B. Jordan) arrives in Monroeville, Alabama, to take the case of a wrongly convicted black man, Walter McMillian (Jamie Foxx), the local white officials who stymie his every move toward justice keep proudly asking him if he’s visited the To Kill a Mockingbird museum, since this is the town where the story is set. No one seems aware of the irony of championing a story that attacks racism while they are fiercely committed to furthering it. That discordant motif establishes the real conflict in this and other legal dramas about racism (Marshall, Ghosts of Mississippi, Amistad, A Soldier’s Story): Movies extolling racial tolerance are dusty museum relics that exonerate us from the responsibility of fighting current injustice.

Movies about racial injustice can make us feel like we’re being scolded more so than other kinds of legal dramas. Dark Waters exposes corporate greed. The Verdict reveals infamy in the Catholic Church. The Rainmaker shows the callousness of insurance companies. These villains are faceless entities sequestered on top floors of tall buildings. Pharmaceutical, tobacco, energy and Wall Street companies destroy the health, lives and finances of millions of families. They get heavy fines and we feel some sense that justice has been done, even though we know that those fines barely affect their bottom line and that those responsible for these evil acts go merrily home at night to their mansions. PG&E was the villain of 2000’s Erin Brockovich, having to pay $333 million to the people whose water it knowingly contaminated with hexavalent chromium. Did the company learn its lesson and become benevolent? In 2019, it filed for Chapter 11 as a result of its alleged $30 billion culpability in California wildfires. The bottom line is the villain in these legal dramas and the bottom line cannot be vanquished.

Albert Finney and Julia Roberts in the 2000 legal drama Erin Brockovich.

But films about racism are more intimate in their accusations because we know that racism can’t flourish without the indulgence of the people. Its mere existence is an indictment of all of us: We’re not doing enough to choke off its oxygen. That’s not a scolding but a reminder that, though some may not be directly affected by racism, millions are. It’s the American ethos to insist that everyone is treated fairly and has equal opportunities under the law. To stand by and do nothing — or worse, insist that inequities don’t exist — makes us complicit.

One genre convention that allows the viewer to ignore responsibility is setting the story in the past. When the wrongfully accused black men in Just Mercy and Marshall are freed at the end, we can rejoice that the bad ol’ days of open racism are over. We are redeemed, hallelujah! At the same time that the movie is telling us about the overwhelming foundational racism in our judicial system, it implies that justice will always prevail, that faith in the American judicial system will be rewarded — eventually. This hyperbolic fantasy distracts us from the real point of legal dramas about racism: In our law books, justice is indeed blind to personal bias, but in practice, the law defaults to its practitioners’ prejudice toward race, social class, gender, nationality and religion. That’s why the Trump administration has devoted so much effort to appointing judges who carry Trump’s values. He has seen 187 of his nominated federal judges approved, including 50 circuit court judges, more than any other recent president. That is how systemic racism is silently and ruthlessly perpetuated.

Just Mercy, which opens nationally Jan. 10, is a riveting, infuriating and inspiring story that focuses on three black men on death row, two of whom are innocent of any crime and a third who, if he were white, never would have received the death penalty. While the movie details how race led to their wrongful but inevitable conviction, it also warns of the dangers and inadequacies of capital punishment. The overwhelming case against capital punishment is so well documented, it’s shocking that 29 states still use it. The death penalty costs more than life without possibility of parole, it executes innocent people, it’s racist in application, it’s not a deterrent to other murderers, and so forth. The guilty conscience of many U.S. Supreme Court justices who have reversed their opinion about the death penalty after decades of hearing such cases was expressed by Justice Harry A. Blackmun: “The death penalty experiment has failed … I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.” Despite all rational evidence, the death penalty exists to mollify irrational voters fueled by hubris and hate. Just Mercy convincingly shows that capital punishment allows us to bury our sins alongside the bodies of the innocent.

How effective Just Mercy is depends on how willing the audience is to look around and see the same injustice breeding today, in the shadows with the same hapless victims. What can we do? To start, maybe not elect politicians whose racist policies try to restrict voting by minorities or who openly solicit racist organizations with comments like “There are good people on both sides.” Read More How ‘Just Mercy’s’ Editor Drew Emotion From a Courtroom Scene

This story first appeared in the Jan. 8 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.