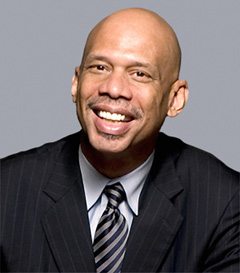

Kareem takes a hard look at the messiahs of ESPN

By Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for Esquire.com

Kids need heroes. Heroes provide models of exemplary behavior to emulate. Heroes inspire kids to achieve more than they thought they were capable of, to find strength when they thought they didn’t have any more, to follow a code of moral conduct when it would be easier and maybe more popular not to.

Kids need heroes. Heroes provide models of exemplary behavior to emulate. Heroes inspire kids to achieve more than they thought they were capable of, to find strength when they thought they didn’t have any more, to follow a code of moral conduct when it would be easier and maybe more popular not to.

But when it comes to sports figures, Americans seem a little confused about what defines a hero.

While I, like thousands of other professional athletes, can feel pride in what we’ve accomplished on the court or field or diamond, most of us cannot claim that we did anything heroic. We were well paid. To be a hero means to risk something considerable in order to accomplish a goal that serves a greater good than the individual. It’s not even important that you are successful, merely that you sacrificed something to try to make things better for someone other than yourself.

Lots of athletes talk about all their sacrifices. “I practiced when everyone else was going to parties,†they complain. Boo hoo. No one made them give up a balanced childhood. And they weren’t “sacrificing†in order to improve the world or their community, just themselves. Reality shows are filled with contestants who claim they are only in it “because of my family†or “for my children.†More bullcrap. They risk nothing in the hopes of a great reward. Sure, they might use the money to help their families, but in the end, they want the spotlight, the acknowledgement, the adulation. That selfish desire is what motivates them, and that selfish desire is what makes them Not Heroes.

In general, professional athletes aren’t any better. Yet, why do we persist in turning athletes into heroes? One reason is that they embody an important aspect of the American Dream. Many professional athletes come from economically depressed backgrounds. Yet, through enormous discipline and dedication, they have made themselves into successes. They now have lots of fame, friends, finances, and fans. Every child’s dream.

While we should applaud them for their achievements, we shouldn’t yet elevate them to the status of heroes. Being a hero depends on what they do next.

Here’s what I mean:

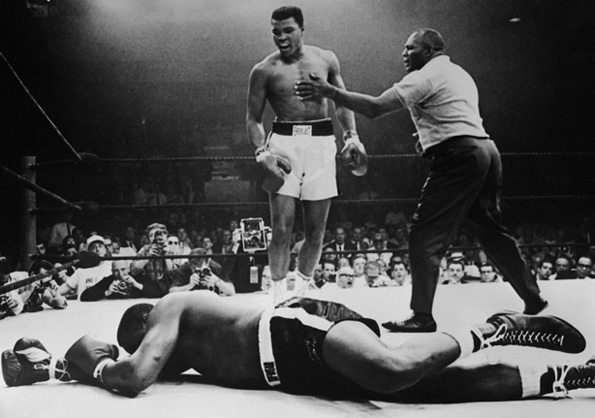

Getty Images

Muhammad Ali looms over Sonny Liston after the knockout.

In 1964, 22-year-old Muhammad Ali, then Cassius Clay, knocked out Sonny Liston to become the world heavyweight champion. He would go on to become the only three-time World Heavyweight Champion who beat the reigning champ each time.

And yet, not heroic.

In 1967, Ali refused to be drafted into the military due to his belief in his religion and lack of belief in the righteousness of the Vietnam War. As a result, he was convicted of draft evasion and stripped of his heavyweight title. Although he wasn’t allowed to box for the next four years, at the height of his athletic prowess, he didn’t stop fighting injustice. He appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned it in 1971. Whether or not you agree with Ali’s actions, they were made out of moral convictions and at great personal and professional risk. Death threats followed. He lost his career. And he did this knowing that had he allowed himself to be drafted, he would never have seen combat; he would have been a pampered figurehead for recruiting.

That’s heroic.

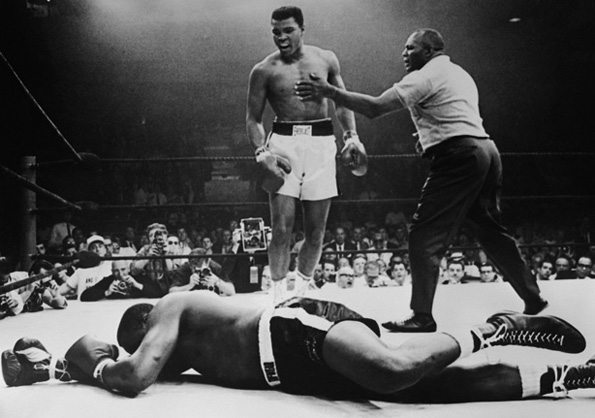

Getty Images

Jackie Robinson and Duke Snider pose as Dodgers and icons.

Jackie Robinson played in six World Series and six consecutive All-Star Games. He was the first black man to win the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949. He was the first Rookie of the Year. In 1997, he became the first pro athlete to have his uniform number retired.

Still not heroic.

In 1947, he braved death threats and endured actual physical assault when he became the first black player on a major league baseball team since the 1880s.

Heroic.

Getty Images

The statue erected in Pat Tillman’s memory in Glendale, Ariz.

NFL safety Pat Tillman was the definition of scholar-athlete. He had a 3.85 GPA and was awarded numerous academic honors. He also helped Arizona State have an undefeated season that put them in the Rose Bowl. He turned pro and was enjoying a successful football career.

Admirable, but not heroic.

In 2002, Tillman was offered a $3.6 million contract. His brother, Kevin, had signed a baseball contract with the Cleveland Indians. Both men refused the contracts in order to join the army following the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. Pat was killed two years later in Afghanistan by friendly fire.

Heroic.

Michael Phelps has won 22 Olympic medals, more than anyone in history. In the 1996 Olympics, gymnast Keri Strug amazed the world by performing a vault despite her injured ankle, thus guaranteeing the team’s gold medal. Both were hailed as heroes and appeared on talk shows, the cover of Sports Illustrated, and in commercials. Both are exemplary athletes that young athletes should emulate—when it comes to athletics. But neither is a hero simply because of their sports achievements. They were motivated by a desire to win and were rewarded handsomely for their efforts. “Bring home the gold for America†has a nice sentimental ring to it, but the reality is that America doesn’t really benefit from their winning as much as they do individually.

Why does American culture persist in pimping athletes as heroes? The answer is the same as it is to most questions regarding popular culture: money. With an athlete as a hero, endorsement deals follow. There’s sports equipment to sell, grooming products, clothing, cars, fast food chains, and on and on. I’m not against endorsements because it makes fiscal sense to use a familiar face to get attention for your product. What I am against is the cynical and expedient manufacturing of sports personalities as heroes that children should emulate. Because the problem with that is that it’s difficult for children to distinguish between admiring athletes’ achievements in their sports and emulating their private lives.

When we see professional athletes riding around in $200,000 cars, draped in layers of gold jewelry, and nip-slip models on each arm, we’re selling sizzle not steak—vapid consumerism over valuable commitments. Of course, not all—not even most—athletes are like that. Most have homes and families and backyard barbeques. But that doesn’t make for exciting photos in the press. Those aren’t the glamorous ones our children see on posters.

Getty Images

Duke Snider, signing autographs in 1963.

It’s always great to find out that your sports hero actually is a great person. I had that experience in 1980 when I went to Dodger Stadium for the celebration of Duke Snider’s induction into the Hall of Fame. I had with me some photos that I had taken with my Brownie Star Flash camera at ‘picture day’ at Ebbets Field in 1956. I was nine years old. The Duke signed my photos of him and took a few minutes to chat with me. He was grateful to be honored but he remained humble and accessible at all times while the day progressed. I felt that my choice of him as a sports hero was definitely a wise choice and one that I cherish to this day. I’m sure many kids today feel the same way when they get an autograph.

Most professional sports teams have their athletes doing charity work, which is then publicized to make the team look like a contributing member of the community. Which they are. When a pro athlete walks into a hospital and puts a smile on a sick kid’s face, that’s a wonderful contribution, no matter the motive. However, the motive is what makes a hero. Doing it out of obligation or contractual duty or even to look good in the press doesn’t diminish the good—but it does tarnish the act.

Getty Images

“I learned fast you can go from being an international hero to being a reference in a joke on a late-night talk show.”

—Michael Phelps

In the past few years we’ve seen plenty of professional athletes fall from grace in the public eye. Kobe Bryant and Tiger Woods had marital problems, Lance Armstrong, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Marion Jones accused of doping, Pete Rose gambled, Michael Vick engaged in dogfighting—the list goes on, including every kind of crime from rape to murder. “I learned fast you can go from being an international hero to being a reference in a joke on a late-night talk show,†said Michael Phelps after the publication of the infamous photo showing him with a bong.

The problem is that we shouldn’t be hailing athletes as heroes in the first place. We should be celebrating their impressive achievements in their sports. And that’s all. They are entertainers, trained to play their sports, not to be role models for our youth. Athletes inspire us to become better athletes; heroes inspire us to become better people. Let’s not confuse the two.

In 1980, 50,000 people marched through the streets of Paris in mourning. Who were they grieving over? French existential writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre was the first person to voluntarily refuse the Nobel Prize (in 1964 for literature) because he felt it would change him as a writer and that it would exasperate the cultural differences between Eastern and Western culture. Wow! For a writer to turn down the most prestigious literary award in the world on principle is admirable. He gave up a lot of money ($1.2 million in today’s market) as well as the potential sales of books he might have had if he’d climbed on that publicity machine. Instead, four years later, at the age of 63, he was arrested for civil disobedience for joining students and workers in strikes. Fifty thousand people marched in mourning for a writer and philosopher and civil dissident. Can you imagine that kind of turn out for any American writer, let alone philosopher?

But maybe we should start imagining it. And if we can imagine it, maybe we can start being more selective in choosing our heroes, based on the content of their character rather than batting averages, field goals scored, or touchdowns scored.

And Now, a Poll!

1. Be they athletes, coaches, politicians, or family members, we want to know: Whom do you consider a hero? Fill in your own answers, click here.