It’s easy to dislike Herbie Hancock. The man is 67 and looks 40! (Someone needs to check his attic for that hidden Dorian Gray portrait.) But then you listen to his music and you are immersed in a variety of emotions—love, melancholy, desire, thoughtful introspection—but none of them are alike. In fact, it’s just the opposite. You experience such a broad spectrum of emotion that you feel even more connected to other people, as if you can suddenly fully appreciate and empathize with everyone else’s feelings. If ever a musician was able to create a musical sense of community, Herbie has consistently done that in album after album.

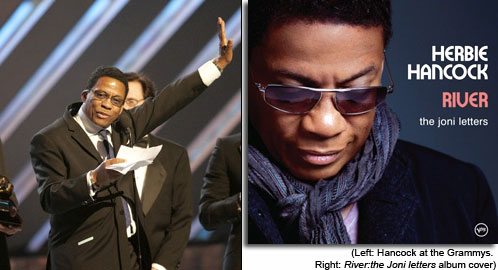

Herbie’s latest album, “River: The Joni Letters,” recently shocked the music world when it won the 2007 Grammy for best album of the year against more mainstream media darlings like Amy Winehouse, Vince Gill, the Foo Fighters, and Kanye West. Jazz has usually been the tolerated stepchild of the popular music world, neglected and ignored, left to play in its room with a few of its misfit friends. Despite that, Herbie’s jazz piano playing has garnered 10 Grammy awards, including two for other tribute albums to Miles Davis and George Gershwin.

It’s easy to see why Herbie was attracted to Joni Mitchell’s songs. Not only is she a dynamic performer herself, but her portfolio of songs is among the most influential in the last 30 years of popular music. You can hardly read an interview with the most famous and respected songwriters of the last few decades without having them mention their debt to Joni. In the movie “Love Actually,” Emma Thompson tells her husband, played by Alan Rickman, that Joni Mitchell “is the woman who taught your cold English wife how to feel.â€Â Using a variety of musical influences from folk to rock—and especially jazz—Joni taught a whole generation around the world how to feel. The genius of Herbie Hancock is he’s using those same songs to teach us all how to feel again—but even more deeply, more richly.

Although all the song titles will be familiar to avid Joni Mitchell fans, some of the songs are more obscure to the casual listener: “Edith and the Kingpin†(with vocals by Tina Turner) and “Tea Leaf Prophecy†(with vocals by Joni Mitchell) to name two. But some of her most familiar songs are also here, including “Court and Spark†(with vocals by Norah Jones), “River†(with vocals by Corrine Bailey Rae), and “Amelia†(with vocals by Luciana Souza).

Even when the song titles are familiar, the same can’t be said for Herbie’s interpretation. His unique gift is for taking what the listener thinks he knows, and presenting it in a way that forces us to re-imagine the song. Many musicians, even jazz performers, fall into the trap of producing an album in which the songs, when played all at once, start to sound disappointingly similar. Herbie deftly avoids that trap by taking risks that defy listener expectations. His interpretation of Joni’s “The Jungle Line,†with poet/novelist/musician Leonard Cohen reciting the lyrics, is one such example. Yet, there is a musical thread that weaves all the songs together as if they were all well-crafted chapters in an intimate novel: the feathery brushing of the drum, the unhurried insistency of the piano, the soulful voices of the singers. Joni says in “Both Sides Nowâ€: “I really don’t know love at all.â€Â But listening to this tender and thoughtful album, we might all feel a lot closer to knowing love.

(Photo credit: Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)