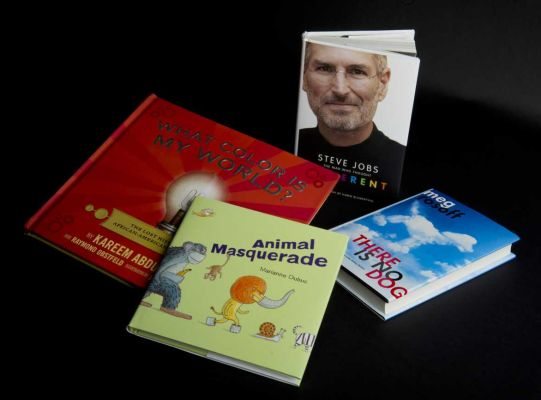

Apple founder Steve Jobs, who died last year, is a rock star to kids who can’t imagine negotiating the world without an iPhone, let alone imagine the existence of a world before cellphones. But it’s that world that may most captivate readers of Karen Blumenthal’s biography, “Steve Jobs: The Man Who Thought Different” (Feiwel and Friends, $16.99; ages 12 and up).

When Jobs and his high-school pals fell in love with computers, it took days or weeks of dedicated fiddling to produce an amusement less sophisticated than the cheapest drugstore toy today. They would, for example, “write small programs on punch cards that prompted the computer to beep every three seconds.” Although their machines did not have enough memory even to do simple math, within a few short decades, they would dream up and bring to vibrant life desktop computers, laptops, the iPod and the iPhone.

Chronicling the ups and downs of Jobs’ storied career, the biography clearly intends to hold up Jobs’ philosophy — living each day as if it were your last — as a model, even while acknowledging Jobs’ flaws, especially his rough handling of other people. Blumenthal’s sharply focused thumbnail comparisons between Jobs and his friends, collaborators and competitors — notably Apple’s genius engineer Steve Wozniak and Bill Gates of Microsoft — may well prompt young readers to look around at their own friends and wonder: “What kind of people are we? Can we grow up to do important work?”

Innovators and inventors are also the subject of basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s “What Color Is My World?: The Lost History of African-American Inventors,” written with Raymond Obstfeld and illustrated by Ben Boos and A.G. Ford (Candlewick, $17.99, ages 8-12). Young Herbie and Ella are disappointed with the dilapidated state of their new house, and cranky with the didactic handyman, Mr. Mital, who seems intent on instructing them in African-American history.

“There’s more to our history than slavery, jazz, sports and civil rights marches,” he insists. But he quickly gains their attention with stories of little-known inventors, which appear around them in foldout pages, with notes and peanut-gallery remarks penciled in by the kids. Some developments were life-changing, like open-heart surgery or food preservation, and some pure fun. The Super Soaker squirt gun, for example, was invented by Lonnie Johnson, a nuclear engineer who also invented the Johnson Thermoelectric Energy Conversion System — “probably a lot more important than the squirt gun,” Ella observes, “but hey, I’m a kid!”

Meg Rosoff has written several oddball and utterly compelling young-adult novels, and “There Is No Dog” (Putnam, $17.99, ages 12 and up) is her best yet, for it is laugh-out-loud hilarious. The premise is that God is a teenage boy. That would explain a lot, wouldn’t it? This God is surly and self-involved, has little attention span, and even less ability to sort out the mess he set in motion. Who hasn’t occasionally wondered, as Steve Jobs reportedly asked his pastor about children starving in Africa, “Does God know about this?”

God, or Bob, as he is known here, has a beleaguered administrator, Mr. B, who does his best to keep the whole chaotic mess running after Bob’s first flurry of creative inspiration: six days and . . . fffttt, time to kick back. Mr. B doggedly attempts to answer mankind’s prayers, while the skirt-chasing Supreme Being is deaf to all but the comeliest petitioners. It’s a difficult premise to sustain and has the potential to offend all kinds of people, but Rosoff has the chops to pull it off, and any reader who can get past the idea of God being ruled by adolescent hormones will find truly wonderful theological possibilities.

At the outset of Marianne Dubuc’s charming “Animal Masquerade,” translated from French by Yvonne Ghione (Kids Can Press, $16.95, ages 3-8), a lion contemplates a party invitation and wonders what kind of costume to wear, which sets the story in motion: The lion goes dressed as an elephant, the elephant goes dressed as a parrot, the parrot as a turtle, and so on, in a classic picture-book chain. Dubuc’s transformations are inspired — the flamingo’s neck becomes the giraffe’s neck, the giraffe’s neck becomes a millipede’s body — and the book goes on long enough to become truly silly, slipping in sassy asides, printing the little upside-down bat’s text upside down, intoxicated with its own audacity and generally indulging in the kind of carnival mayhem that a great masquerade party invites. The tradition of masquerade is to allow a suspension of the rules, and in its gentle, toddler-friendly way, “Animal Masquerade” does just that.