Historians routinely praise Thomas Jefferson as one of the smartest men of his time. He was educated, well read, a prolific writer (hey, he wrote the Declaration of Independence!), a dedicated statesman, and one of the most powerful men in the country. One can only wonder at what kind of self-confidence and courage it must have taken for someone at that time to write to Jefferson to scold him for his hypocrisy.

Yet that’s exactly what Benjamin Banneker did. What makes this outrageous act even more courageous is that Banneker was a black man. And what makes the act historic is that the two men became friends.

But Banneker’s place in history would have been assured even if he had never written to Jefferson. His achievements were already legendary by the time he wrote his first letter.

Banneker was born in Maryland in 1731. His father, Robert, had been an African slave, but he bought his own freedom and married Mary, the daughter of an Englishwoman and a free African slave. Banneker was raised on his father’s farm and briefly attended a Quaker school. But the limitations of his formal education in no way limited his pursuit of knowledge. His love of reading prompted him to teach himself literature, history, and math. The extent of his ability to teach himself became evident to everyone else when, as a 21-year-old man, he saw his first pocket watch. Young Banneker’s fascination with the watch resulted in his dismantling it and rebuilding it several times over the next few days. He then borrowed books on geometry and Isaac Newton’s laws of motion. Soon he was hand-carving every piece of the watch in order to build a much larger version. When he completed the clock — the first clock ever built in the United States — it continued to keep time for 50 years.

Banneker’s curiosity next took to the heavens. He taught himself astronomy and was soon predicting everything from the times of sunrises to eclipses. In 1792, he wrote his first almanac, in which he predicted weather changes and offered farming tips and medical advice. He sent a copy of his almanac to then-Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, along with a 12-page letter pointing out that not only were blacks intellectually equal to whites, but that Jefferson’s own Declaration of Independence implied that they should have the same rights. He compared slavery of the blacks to the enslavement of the American colonies by Britain. Banneker was so eloquent that we should read his actual words to Jefferson:

“Sir, how pitiable is it to reflect, that although you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of Mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of these rights and privileges, which he hath conferred upon them, that you should at the same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.â€

Their correspondence was published as a pamphlet, then reprinted in Banneker’s 1793 almanac. These almanacs were supported by abolition societies in Maryland and Pennsylvania as examples of the equal intellectual capabilities of blacks. Jefferson and Banneker continued to correspond over the next several years. In fact, it was Jefferson who recommended that Bannecker be part of a distinguished group formed to help Major Pierre L’Enfant draw plans for moving the nation’s capital city from Philadelphia to what would eventually become Washington, D.C.

Due to political infighting, L’Enfant left the project and returned to France, leaving Banneker and the others without any written plans. However, Banneker quickly astonished everyone by drawing the plans from memory in two days. These plans were the basic blueprint of streets, monuments, and buildings that comprise current-day Washington, D.C.

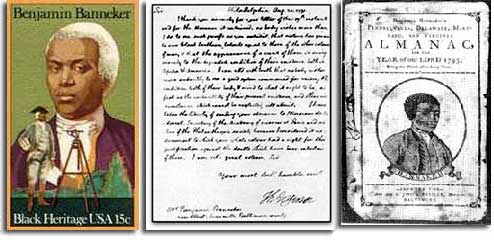

Banneker died in 1806, having achieved the honorific title of “the first Negro Man of Science.â€Â In 1980, a Benjamin Banneker postage stamp was issued by the U.S. Postal Service.