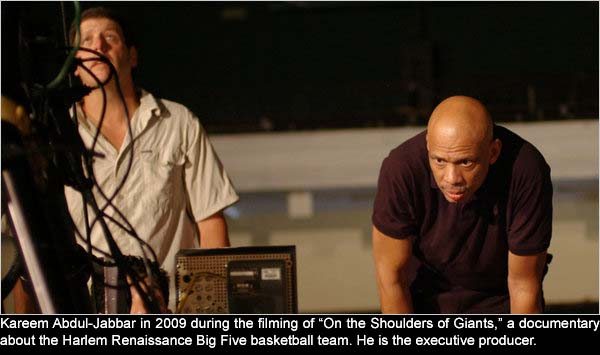

On Thursday in Los Angeles, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar will screen his documentary, “On the Shoulders of Giants: The Story of the Greatest Basketball Team You Never Heard Of,†which tells the story of the legendary Harlem Renaissance Big Five.

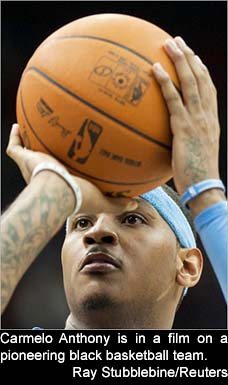

Among the film’s many outstanding witnesses is Carmelo Anthony, the star forward of the Denver Nuggets. In his four appearances in the documentary, which will have its premiere on Tuesday on video on demand, Anthony is thoughtful and perceptive and offers an appreciation of history. His demeanor is a refreshing departure from the image that has been portrayed in the context of the speculation about his potential trade or free agency.

Among the film’s many outstanding witnesses is Carmelo Anthony, the star forward of the Denver Nuggets. In his four appearances in the documentary, which will have its premiere on Tuesday on video on demand, Anthony is thoughtful and perceptive and offers an appreciation of history. His demeanor is a refreshing departure from the image that has been portrayed in the context of the speculation about his potential trade or free agency.

Anthony does not talk in the documentary about where he will or won’t land or where he wants to play and for how much. Instead the Brooklyn-born Anthony talks about a collection of athletes; a place, Harlem, known as the heart and soul of basketball; and how the Rens were part of the foundation on which basketball history was built.

The Rens, under the ownership of Robert Douglas, became the first black professional basketball team in 1923.

In one part of the documentary, Anthony talks about the precision of the Rens, the teamwork distinguished by suffocating defense, fast breaks and pinpoint passing.

“Back then, for guys to not put the ball on the ground, that’s hard to do even now,†he said. “Make five passes without the ball hitting the ground, hitting people cutting through the lane without the ball hitting the ground — that’s tough.â€

The Rens were largely invisible actors in a sport that itself was on the margins of American sports culture.

In 1939 the Rens won the first world professional basketball championship in Chicago. Screaming news in the black press, the Rens’ victory over the Oshkosh All-Stars was all but ignored by the white press.

Fast-forward to 2011, when the sports news media are obsessed with Carmelo Anthony’s potential movement. Not a day has passed in the last month that Anthony has not been the subject of speculation: Los Angeles? New York? New Jersey? Denver?

Anthony’s generation is portrayed as richly compensated young men who eschew history and live in the moment and for the moment, but he understood that the hardships of the past contrast with the lavish lifestyle of today’s athletes. He expressed a subtle appreciation for what his basketball ancestors endured simply to scratch out a living playing a game that now pays out multimillions: the name-calling, the physical abuse and humiliation, then having to perform at a high level.

On the other hand, pressure is relative. While black athletes of the Harlem Rens’ generation struggled for equality and fairness, the contemporary athlete attempts to find a way to get the most out of a narrow window of tremendous earning potential.

Anthony talked recently to FanHouse.com about the pressure he felt and the intense scrutiny of his possible free-agent status this summer.

“I think it takes a strong-willed person, a strong-minded person, to deal with the stuff that I deal with and still go out there and go to work every day and perform on a nightly basis,†he said. “I really don’t think an average person can walk in my shoes. I don’t think that.â€

The Harlem Rens could. And did. The Rens often played eight games in a week, many times two a day. They played all comers, traveling as far as 200 miles for a game.

When they were refused housing accommodations because of Jim Crow laws, the Rens slept on the bus. When they were turned away from restaurants, they ate cold meals.

They drove buses and cars through the segregated South and the often hostile North. They endured the profanities, the physical confrontations, just to eke out a living.

“Now we, sorry to say, we complain about playing back to back, you know, two games,†Anthony said in the documentary. “Now we fly in private jets. You’ve got catered food on the plane, you’ve got meals when you get to the hotel, meals before the game. Back then you didn’t have any of that.â€

The contemporary athlete needs these lessons to help understand that an older generation endures trials and tribulations so that another generation can prosper.

The source of Anthony’s pressure is simply deciding which team will pay him many millions of dollars to play basketball.

Pressure? Where is the pressure?

In his final appearance in the documentary, Anthony expresses an understanding of the debt his generation of athletes owes to the Rens and other pioneers.

“Guys like Sweetwater Clifton, all the older guys, we couldn’t thank them enough,†he said.

History lessons are meaningless unless applied in a contemporary context.

Strength comes from knowing who and what came before, what races they won and lost, that they had to deal sometimes with life and death circumstances.

During a recent interview in New York, Abdul-Jabbar said: “When you have a connection to your history, you have a perspective that gives you a lot of confidence. It gives you an idea of where you need to go from here. It’s not like they just dropped you out of a plane. There’s a connection there; young people absolutely needed that.â€

Even a young superstar athlete like Anthony, who knows now whose shoulders he stands on.