When you watch TV shows today, it’s not uncommon to see black doctors charging up the paddles and shouting “Clear!” or “Somebody get me a rib-spreader, stat!” When I was growing up, however, a black doctor on TV was a rarity. A black nurse, sure. Sometimes. There was the sitcom “Julia” (1968-1971) starring Diahann Carroll, groundbreaking because it was one of the first TV shows to feature a black woman in a non-stereotypical role of nurse. Before that, black women usually portrayed servants. And that was only forty years ago!

I can’t help but think how hard it must have been for black children 140 years ago just coming out of the Civil War era with very few role models to inspire them to become whatever they dreamed of becoming. That’s what’s so remarkable about Dr. Daniel Hale Williams’ journey to becoming the first surgeon, black or white, to perform open-heart surgery—and have his patient make a full recovery.

Born in 1856 in Pennsylvania, Williams didn’t start out with a burning need to become a doctor. He started out as a barber. But his fascination with a local doctor got the better of him and he soon became that doctor’s apprentice.

After two years he entered what is now known as Northwestern University Medical School, graduating in 1883. He opened his own practice in Chicago, treating many of his black patients in their homes, sometimes even performing surgery on their kitchen tables. Because of the unsanitary nature of the almost battlefield-type conditions, he had to become very informed on the latest medical discoveries in sterilization and antiseptic procedures. His reputation grew, resulting in him becoming a surgeon on staff as well as a clinical instructor in anatomy at Northwestern. Soon he was focusing his energies on creating an interracial hospital, the Provident Hospital and Training School Association, a 12-bed hospital and school that trained black nurses and used doctors of various races. But Williams’ claim to fame occurred on July 9, 1893 (the same year of Gandhi’s first act of civil disobedience halfway around the world, and the year that Colorado granted women the right to vote).

A young black man, James Cornish, had been stabbed in the chest during a bar fight. He arrived at Provident in shock and near death from loss of blood. Williams decided the only possibility of saving Cornish was to open the chest and operate internally. This was almost never done, because the risk of infection was so high as to practically guarantee death. However, 51 days after the operation, Cornish left the hospital—and lived for another 50 years.

When the American Medical Association refused to admit black doctors, Williams co-founded the National Medical Association for black doctors. In 1913 he became the only black member in the American College of Surgeons. Until his death in 1931, he continued to push for more hospitals for African Americans. If you’re African American, it makes you wonder how many of your ancestors got medical care and lived because of him. And because they lived, you are here. The heart I’m most grateful that Dr. Williams opened was his own—for all of us.

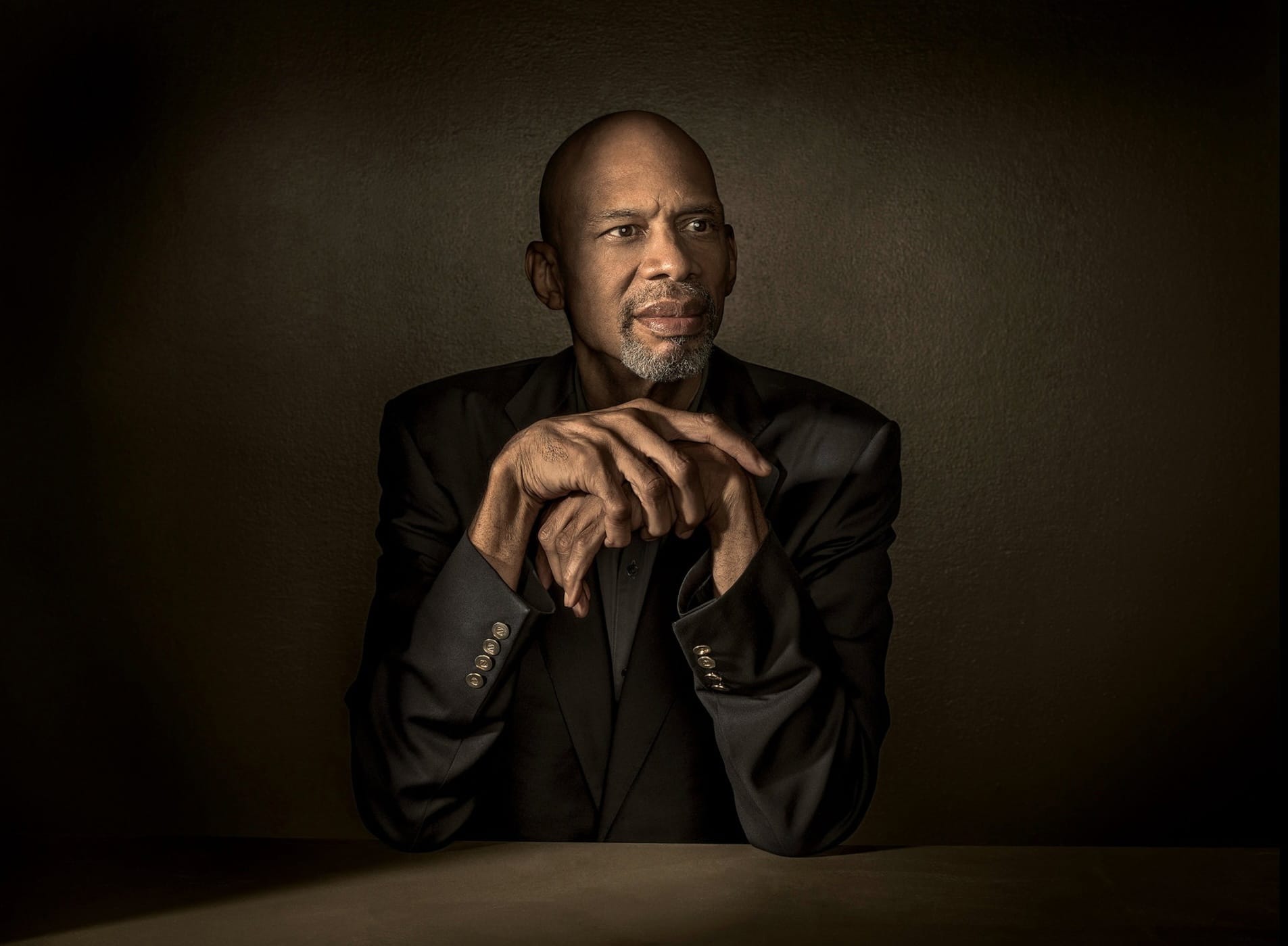

Photo Credit: Black Inventor