Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Travels from Court to Classroom to Highlight History of African-American Inventors

The NBA all-star says he hopes young students realize the power and influence they can achieve in STEM-related fields

Basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wants kids to stop looking up to basketball legends.

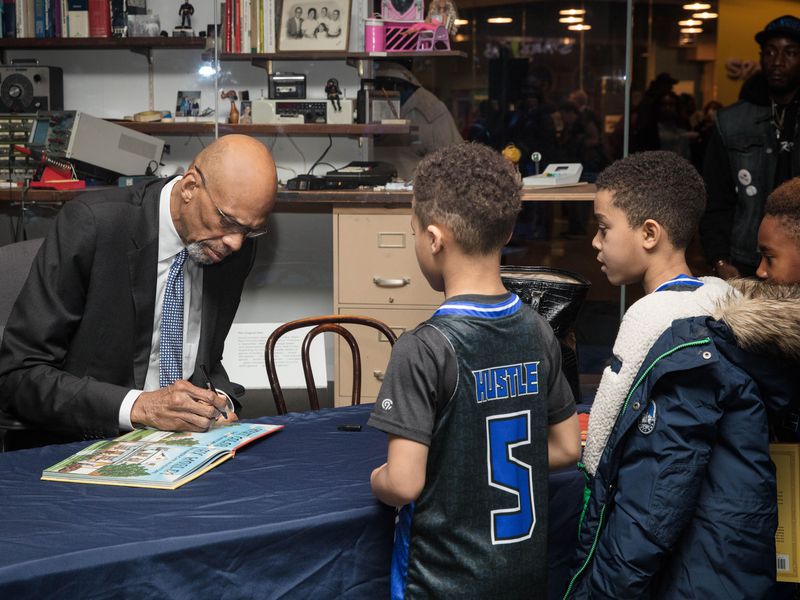

Recently at an event hosted by the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, Abdul-Jabbar sat down with Ray Fouché, the director and associate professor of Purdue University’s American studies program. Discussion topics included his iconic skyhook shot, the importance of social activism and his 2012 children’s book, What Color is My World: The Lost History of African-American Inventors.

Abdul-Jabbar’s New York Times bestseller, co-authored with Raymond Obstfeld and illustrated by Ben Boos and A.J. Ford, introduces young readers to impactful black inventors and innovators, like Percy Julian, the developer of cortisone, whose stories are largely overlooked or ignored by history. Take Lewis Latimer, for example. His groundbreaking work on Edison’s light bulb not only aided the inventor’s patent efforts and his soar to fame, but also made electric lighting far more economical. Yet Latimer’s contribution is rarely mentioned as part of the Edison story.

In his book, Abdul-Jabbar features inventors that have played a role in each of our lives–from our taken-for-granted methods of communication to our cherished summertime memories. There is the unheralded work of James West, the inventor of the cell phone microphone, and Charles Drew, blood transfusion researcher and the developer of blood banks, and Lonnie Johnson, inventor of the famed Super Soaker.

For Adbul-Jabbar inspiration to tell these stories began during his writing career which took shape post-NBA. While researching his other books, such as On the Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance, he came to realize that much of history had forgotten the staggering scientific contributions of black Americans. Throughout his own life, he had encountered other racial stereotypes. So often, he noticed that the expectation for African-American success was stereotypically categorized–African-Americans were assumed to possess athleticism or a knack for rhythm and blues, but rarely an aptitude for rocket science or astrophysics.

“The whole idea Europeans had that Africans could not give anything worthwhile to the scientific disciplines got a foothold in people’s imaginations,” he said in the discussion. “It’s applied to every generation of young black Americans, and we have to change that.”

It is his belief that fighting injustice begins with providing kids opportunities to learn and eventually cultivate a stable career. Because the future of STEM is awash in possibility, the greatest opportunity for success lies in science education.

For its part, the Lemelson Center is working to bring these types of inspiring conversations to the communities that need it most. In a new approach to public engagement, the center reserved half the tickets to the recent program for minority students, teachers and athletes from local schools and youth organizations. Says Will Reynolds, Lemelson’s Finance and Administration Officer, the center wanted to ensure that those it felt would be impacted the most by the content of the discussion were able to attend.

A major goal of the series, says Reynolds, is to “present stories about diverse inventors so that the audiences [the center] strategically wants to reach can see themselves in the historical narrative of American invention.”

Right now, young black students make heroes out of celebrities like Beyoncé, Denzel Washington or LeBron James, says Abdul-Jabbar. He hopes his recent book and the work of his Skyhook Foundation will help young students realize what they can achieve in STEM-related fields. The foundation brings children from underserved Los Angeles communities to Camp Skyhook in the Angeles National Forest. For five days, the students experiment, learn from today’s leaders in science and explore the possibilities in math and science-based careers. “When they get heroes more like George Washington Carver and Thomas Edison,” Abdul-Jabbar says, “we have achieved ultimate success.”

Reynolds agrees. Programs such as Skyhook and initiatives like Innovative Lives not only introduce students to other types of heroes, they provide mentorship and direction. “What we can do is twofold,” he says. “One, we can provide them with the motivation, and then secondly, provide them with the pathway.”

This is especially important because, as Abdul-Jabbar and Fouché see it, inspiring children to pursue STEM doesn’t just position them for personal success. It’s key in promoting greater social development. “The economic power you get from that type of knowledge enables you to affect change,” says Abdul-Jabbar. In this way, says Fouché, STEM is a powerful tool to fight racial, social and cultural injustice.

Read more at Smithsonian.com